|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Flute and Flute Music of the North American Indians

AcknowledgmentsI am most thankful to Dr. Bruno Nettl for his advice and guidance throughout all stages of this thesis. My thanks to Dr. Demitri Shimkin for his help which greatly contributed to this study. I am most grateful to Dr. George Herzog for granting me the permission to use his valuable recordings, and to Dr. Frank Gillis and the entire staff of the Indiana University Archives of Traditional Music for their assistance during the first phase of my research. My appreciation to Dr. Edward Wapp for his interest and contribution. My sincere gratitude is due to my husband Howard Buss, and my good friend Ted Solis for their moral support, their patience and help in proof reading the manuscript. Introduction: Problems of ResearchThe flute occupied an important and unique role in the culture of the North American Indians. Its use was confined to specific aspects and events of their cultures. With the drastic changes that Indian cultures underwent in the last forty years — frequent dislocation, diffusion and acculturation — many cultural traits completely or partially disappeared, among them Flute-Lore. Consequently this study is almost entirely based upon material gathered before 1935. At all times, flute making and playing was specialized and the privilege of a few, so that ethnographical information about the flute was not readily available. This problem does not exist concerning vocal songs or stories which are performed and shared by all. A second factor was responsible for the scarcity of research material about the flute: in many instances among the American Indians magical and supernatural power was attributed to the flute. Secrecy surrounded the making and use of the flute, a fact which often prevented access to knowledge or study of flute-lore by other tribesmen or outsiders. (A discussion of this aspect will be presented later in this chapter.) The existing ethnography about the flute presents further problems. First, interpretation of the material. Accounts and descriptions by natives of their own culture are variable as are the informants themselves. Even among members of one generation within one village or town one finds great variation. The attempt to bring the diverse information into focus inevitably leads to some speculation and perhaps to occasional distortion. Secondly, the American Indian culture embodies a spectacular complexity of beliefs and mythology. In each tribe one finds a network of clans, fraternities and other societies each of which had a long tradition of customs, taboos, ceremonies, costumes and a rich and intricate mythology. It is the enormous complexity of beliefs and rituals on the one hand, and variation in rendition on the other, which create a true challenge for the researcher to acquire a full understanding of the place of the flute in American Indian culture. In the course of my discussion I will provide examples demonstrating the role of the flute in certain tribes. The available material on the flute seems to have been gathered somewhat unevenly. For various reasons some tribes were more thoroughly investigated than others. For example, a large number of monumental studies have been published on the tribes of the Southwestern U.S., whereas in the Eastern and Southeastern regions much less research was done. This does not mean, of course, that other tribes did not share some of those beliefs or at least that they did not hold beliefs of the same order, which will be discussed here. The term flute, flageolet, and whistle are often used quite loosely by folklorists, ethnographers and others, however admirable, who gathered material about American Indian culture. Not being musicians, they were not aware of the distinct differences in structure and manner of playing of all three instruments. The flute (transverse flute) and the flageolet (a type of recorder) share similar meaning and use in American Indian culture. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, they are treated as one. The term flute will be used here to refer to the instrument in general, for it is seldom possible to determine from the sources whether a flute or flageolet is referred to. The role and connotation of the whistle, however, greatly differ from that of the flute and flageolet. Any material about the whistle and accounts of rituals involving whistles was not included in this study. The following pages will sketch the main aspects of the meaning of the flute in the American Indian culture. Within the limited framework of this study one can only hint at the richness and complexity of flute-lore which existed in the past. Much more evidence is needed in order to conduct a large-scale research project of this fascinating aspect of American Indian culture. The Role and Meaning of the Flute in North American Indian CultureRegardless of great variation among cultures, the flute seems to be almost universally viewed as a phallic symbol. Throughout the world, the flute is associated with fertility, birth, life, and death and is used in numerous rituals centering around these subjects.2 Among the American Indians as well, the flute, as a phallic symbol, became “medicine.” Magical power was attributed to it and it was believed to influence fertility and related concepts. American Indian culture produced a rich mythology concerning the origin of the flute and legends demonstrating its supernatural power. The boundaries between myth and real life became blurred; thus, in rituals connected with the flute one witnesses a curious synthesis of the two. Various connotations are associated with the flute, all of which are tightly linked with a central subject, namely Life. In the course of this chapter I will discuss its symbolism and involvement in rituals centering around human fertility, general fertility in Nature (warm weather, rain, good crops, etc.), and its connection also with war, life, and death. 2 See, for example, Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History vol. 36, 37; [Sachs 1940], many examples cited on pp. 44–45. Human FertilityThe flute seems to represent particularly male fertility in North American Indian culture. Due to the limited scope of this study, a discussion of the psychological reasons for this fact will be omitted. Briefly, the shape of the flute and manner of performance are the major, though not the sole factor. As Curt Sachs stated “Primitive man cannot overlook the resemblance between a pierced straight instrument and the penis” ([Sachs 1940], p. 44). From the mythology, as well as ethnographies gathered throughout North America it becomes evident that flute playing was restricted to men only.3 Even in the Corn Grinding Ceremony of the Pueblo Indians, a ritual performed only by women, accounts describe a man playing the flute to accompany the singing and dancing of the women.4

3 Throughout the examined material only one example was of a

woman playing the flute and that only for the purpose of

teaching a boy how to play it. This example is “The Story

of the Origin of the Flute.” [Densmore 1929], p. 62. The making of flutes, however, in principle was not restricted

to males. This stems from the fact that North American Indians

attribute magical power to it. The mythology demonstrates how

flutes were made by shamans and successful dreamers, men or

women, who, according to belief, had direct contact with the

supernatural and were able to attach magical power to the flute.5

Numerous examples of women flute makers can be found in the

mythology, however, there seems to be no evidence of women flute

makers in reality. The following are some examples of legends

involving female flute makers. These also illustrate the nature

of magical power attached to the flute such as weather control,

means of transportation, and luring women. In the story “The

origin of the Flageolet” told by Mandan and Hidatsa informants,

“Granny” (a characteristic mythological “medicine” woman), made

a flute for a motherless boy whom she found and adopted. She

taught him how to play it. The story incidentally does not

explicitly say that in order to teach she actually played it

herself. Granny told the boy to walk in four circles (viewed

as a magic number), each smaller than the other. When the boy

played the flute the snow began to fall ([Densmore 1923] 5 [Grinnell 1923], p. 9 (in notes); [Hassrick 1964], pp. 116, 146–7. An instance which especially brings to focus the magical power attributed to the flute is found in Apache myths and tales. The flute becomes a means of transportation, a fact which Goddard says “is one of the recognized methods of rapid transportation” ([Goddard 1919], pp. 20, 25, 114). In several versions of the story “The Creation Myth” a man who was looking for his missing wife used the flute to travel across the mountains: “He started away, travelling with a blue flute which had wings … he went entirely around the border of the world” (ibid., p. 114). The most direct link between the flute and its magical power and symbolism as male fertility is its use by men in courting. In a story told by the Crow Indians, a young man was in love with a woman, but she rejected him. He then secluded himself in order to seek a vision. A supernatural being appeared to him in a form of an Elk,6 and “blew the flute causing all female animals to scamper toward him.” The man then returned to the village, made a flute duplicating the one he saw in the vision and succeeded charming his beloved ([Lowie 1935], p. 52). Similarly, a young Cheyenne man who was in love would go to a medicine man and ask him to bring his magic power to bear on a flute so that the girl he wanted would yield to his love ([Grinnell 1923], p. 134). The Wind River Shoshone Indians tell: “Once a woman heard a fine flute player who was very ugly on account of a disfigured lip. She was charmed by his playing and joined him at the night without knowing who he was until she discovered his identity when she left him” ([Lowie 1924], p. 311). Among the Sioux Indians shamans were paid to prepare this love charmer. The courting flute of the Sioux is the “Big Twisted Flute” of cedar ornamented with the effigy of a horse ([Hassrick 1964], p. 116). The Sioux claimed that the flute was effective only when accompanied by the magical music of love. The music, so they say, was composed by the shaman “according to instructions received in a dream” (ibid.). The music was sold to the young man along with the magic flute and “if properly executed, the music was irresistable.” According to informant Leader Charge “some flutes were so powerful, that a girl hearing the melody would become so nervous that she would leave her tipi and follow it” (ibid.). In some cases the young man would take his love to the shaman who made the flute. The shaman would blow the smoke of herbs at her and give her medicine to revive her (ibid.). 6 Among several tribes the elk symbolizes masculinity, beauty, virility, virtue and charm. See for example [Deloria 1961], p. 6. So far the symbolism of the flute in connection with human fertility has been discussed. In the following pages the extention of this symbolism into the general fertility of nature will be shown. General Fertility in NatureIn those areas where corn is raised, its symbolic role as a fetish of fertility and welfare is tied in many instances to the symbolism of the flute. Whereas the flute is, by and large, associated with male (not only human) fertility, corn is primarily linked with female fertility and harvest. As far back as 1541 Castaneda noted the use of flageolets in the Tewa Pueblos Corn Grinding Ceremony. In this ritual performed by women only the sound of grinding stones was accompanied by their dancing, singing and a flageolet played by a man sitting at the door ([Hammond-GP 1940]) . A further demonstration of the close relationship between the flute and corn at a much later date can be found in an account by A. M. Stephen, of an initiation into the Hopi Flute Society: “When a young person is brought to look on the flute altar for the first time—he gives a handful of prayer-meal to the man he has chosen for a ‘father.’ The ‘father’ casts the meal on the altar … On the fourth night of the ceremony the novice is admitted to the chambers and is given the ritual corn ear, his ‘mother,’ which he holds throughout the song … The corn ear he places in his mother's house. It insures good flesh and bodily health, and this is why a symmetric ear is always chosen” ([Stephen 1936]). The Blue and Drab Societies, which are now extinct, played a most important role in Pueblo culture. The chief duties of these societies were praying for rain and fertility as well as warm weather and good crops. Since Pueblo Indians live primarily in a desert environment, the absence of rain was a threat to their physical existence. Thus, much of the rich ceremonialism of the Pueblos centered around this preoccupation. One of the most important events which used to take place in Pueblo culture was the Flute Ceremony, occurring in August. It was observed every other year, alternating with the Snake or Antelope Ceremony ([Coolidge-MR 1929], pp. 124–5). Detailed descriptions of the elaborate rituals of the Flute Societies are given by several scholars, such as Hough, Stephen, Fewkes and Parsons ( 1) Hough as quoted by [Coolidge-MR 1929], pp. 140–42; 2) Stephen, as quoted by [Parsons 1939], pp. 843–44; 3) [Fewkes 1894], pp. 265–89; [Fewkes 1896a], pp. 241–55; 4) [Parsons 1925]). The ceremony and mythology are intimately connected, and secret rites were held in the society's ancestral rooms rather than in the kivas where most other ceremonies were held ([Morris-F 1913]). The precise details of the ritual were known only to priests who were the chief performers of the ceremony, and responsible for its transmission to succeeding generations of priests. The flute altar was a shrine covered with drawings and a large number of items, each symbolic of a certain aspect of the ritual (for a detailed description, illustration and discussion of the flute altar see [Fewkes 1895] and [Fewkes 1896a]). On the flute altar tiles was depicted Locust, the humpbacked flute player known throughout the Southwest, and “medicine” of the Flute Society. This intriguing figure is linked with warm weather and fertility, but even more with bravery. In one of the “Emergence Myths” told by the Pueblo Indians of Oraibi, at the “beginning,” people rejected Locust. They “ran arrows through him … and he died.” Later “he came to life again and ran about looking as he did before …” After that people changed their view concerning Locust and announced him “medicine,” the guardian of wounded in war, for “he possesses wonderful powers of renewing his life” ([Cushing 1923], p. 167–8). The Hopi tell about brave Locust. He walked playing the flute when clouds from all directions shot lightning at him, but as he is said never to wink his eyes he was able to withstand the vicious attack and continue to play the flute. Afterwards the “Chief of Directions” concluded: “For sure he is brave, for sure he is a man.” They then announced him “brave and deathless” ([Stephen 1929], pp. 5–6). The Navaho also tell of Locust's bravery: “The clouds shot their bolts through him, and he merely continued to play on his flute” ([Stephen 1930], pp. 88–104). Locust is also a patron of societies established to cure lightning shock, and arrow or gun shot wounds. He can foresee, in dreams such events as war. In Hopi tales, Locust also plays to melt snow if so requested by the snake ([Parsons 1938], pp. 337–8). The various roles given to this character, then, embrace many aspects of life: Fertility, life, weather control for warmth and good crops, and war (throughout the Southwest, war societies are associated with fertility rites and the convocation of rain7). 7 [Parsons 1939], pp. 115, 880; [Parsons 1929], p. 652. Through Locust and other personalities and objects discussed above the flute is associated, then, with warm weather and good crops on the one hand, and survival and bravery in war on the other. Thus in a rather intricate way even the dead are associated with life, rebirth and fertility: the dead are viewed as clouds (“cloud beings”) which are in turn tied to rain and crops (clouds symbolize rain in the Southwestern region8) . 8 [Parsons 1939], p. x.

The association of flute with war, life, and death is not

unique to the Pueblo and Navaho. It is a widespread phenomenon

in American Indian cultures. Among the Fox Indians the flute

was one component of the medicine bundle in the White Buffalo

Dance. In this ceremony, too, one finds themes of curing,

rebirth, and victory over an enemy ([Kidder 1919], p. 37–8). A

principal ceremony of the Winnebago Indians is the Wagigo, the

“Winter Feast” or “War Bundle.” The ritual focuses on success

in war, although it later developed into a general celebration

of thanksgiving. In the rituals the warriors are given the

choice of the best meat. The host himself does not eat but

instead plays the flute ([Radin 1923], p. 430). Chippewa

warriors used to go through the village playing the flute to

signal an enemy's approach ([Densmore 1929b] Among the Wind River Shoshone a unique warrior society existed—the Wiyagait (“does-not-know-anything”) also known as the “Crazy Dog Society.” They went to the battle field armed only with flutes. A warrior tried to hit an enemy on the head with his flute. If he killed an enemy, he became a war chief and threw the flute away (Lowie, as cited by [Parsons 1939], p. 307). In another example of a Shoshone tale, a dispairing lover, deciding that life was no longer worth living became a Wiyagait. Armed only with a flute he attacked the enemy and got killed ([Shimkin 1947], p. 307). Weather ControlFrom legends and accounts of rituals and ceremonies a recurring theme emerges and illustrates one of the cardinal roles attributed to the flute, namely, its ability to control weather. The magical power of the flute was often applied to influence weather. In a Mandan and Hidatsa myth “The Origin of the Flageolet,” Granny, who had made a flute for a boy, instructed him: “play a tune on the flute then lift upwards and revolve your body while circling the mountain each time lower.” The boy circled the mountain four times, following Granny's instructions, and “there was a big blizzard.” The bad weather was brought about in order to punish two hunters. Because of the blizzard they could not see, and were shivering from the cold. Since the weather prevented them from hunting they had not had food for several days and became very weak. They called the boy and begged: “We are in misery and want. Come down and save us.” The boy came down and “rubbing his flute, as if to clean it, made a circle with his arm to the sky. The clouds began to part and the sun shone bright and the snow melted” ([Beckwith-MW 1938], p. 129). In the White Buffalo ceremony of the Fox Indians mentioned before, the flute is part of a medicine bundle. Dispelling storms is included among various duties of the bundle owner ([Kidder 1919], p. 37–8). Locust the humpbacked flute player of the Southwest is believed to have special powers to control weather. As mentioned earlier he is the patron of the Pueblo Blue and Drab societies, which are in charge of performing rituals and ceremonies for the invocation of rain. In the elaborate ritual of the flute ceremony performed by these societies, a complex of symbolic objects and activities take part in the effort to bring rain for good crops. A certain stage of the ritual takes place by the water: “At the spring they sit on the north side of the pool, and as one of the priests plays the flute, the others sing, while one of their members wades into the spring, dives under the water and plants a prayer stick in the muddy bottom. Then taking a flute wades into the spring and sounds it in the water to the four cardinal points …” (Coolidge 1927, pp. 140–42). It is significant to note that the number four, which has a magical connotation in many Indian cultures, is always connected to the flute in rituals and myths as reinforcement of its supernatural meaning. Its involvement is expressed in a variety of ways, such as in ceremonies where the participants circle a place or an object four times, a certain action is carried out by four people at different points in a ritual, or some aspect or procedure lasting four days. Detailed descriptions of the rituals can be found in the sources cited on p. 9 of this thesis. Also in myths, many examples in which number four is involved have been given in the course of this chapter. For example in the Papago legend “story of the Origin of the Flute” ([Densmore 1929], p. 54), in the Mandan and Hidatsa story “Origin of the Flageolet” ([Beckwith-MW 1938], p. 129). Another example can be found in the legend “The Origin of the Courting Flute” told by members of the Dakota tribe ([Deloria 1961], p. 5–7). The Visual Appearance and Structure of the FluteThe visual appearance of the flute is part and parcel of its symbolic role. However, because of the scarcity of material concerning this aspect, it is difficult to gain sufficient understanding of the variety of design and color of flutes in North American Indian cultures. Only occasional comments beyond superficial physical description are scattered throughout existing ethnographies. The following are some general comments; however, much more evidence is necessary before a substantial and conclusive study can be made. One of the first questions which comes to mind is whether guidelines governing flute-making among the Indians have musical or extra musical bases. Testimony of various informants leads to the conclusion that extra musical reasoning is primarily responsible for its construction.

Three factors are the main determinants of pitch and scale

1) Flute length; 2) Number of finger holes and 3) Distance

between holes. The most common number of holes found in North

American Indian flutes is four to six.9 Flutes of three and

seven fingerholes also exist, as well as some with extra holes in

the bottom of the tube. Evidence as to the reason for a certain

number of holes is very sketchy; however, it may be speculated

that the number of holes in some flutes is determined by symbolic

rather than musical reasons. Since four fingerholes are most

common it is likely that the number four, again, plays a symbolic

role. In the myth “The Origin of the Flageolet” from the Mandan

and Hidatsa tribes, Granny, who made a flute from a sunflower

stalk, explains that “the seven finger holes represent the seven

months of winter” ([Densmore 1923] 9 [Morris-F 1913]; many of the sources in the bibliography include descriptions of flutes.

As mentioned earlier some flutes had holes added at the

lower end of the tube. As with some Chinese flutes, these holes

were not used for playing. It is not clear whether those extra

holes were bored for mere decoration or had some other function.

It is not unlikely, however, that some Indian tribes were

influenced by the Chinese. Merriam mentions the presence of

Chinese influence in the latter part of the nineteenth century,

when many Chinese came to Western Montana ([Merriam-AP 1951], p. 368–75). Flutes with such added holes can be found in several tribes.

Densmore describes a Chippewa flute with fix finger holes and

five holes in a line around the end ([Densmore 1929b]

The distance between holes seems to approximate the size of

the maker's hand and fingers or those for whom a particular

flute might be made. Merriam describes how a Flathead flute

maker bores holes in a flute: “… the craftsman places his

fingers on the hollow tube in what seems to be the appropriate

position and burns the holes in the wood …” ([Merriam-AP 1951],

pp. 367–75). The question of the distance between finger holes

needs further study. The holes in many flutes, especially those

of three or four, are equidistant. In a six-hole flute there

often are two groups each comprised of equidistant holes. In

another example Densmore tells about a Yuman flute maker, Captain

George: “he marked places for three finger holes where his

finger rested most conveniently” ([Densmore 1932], p. 26). In

her book The American Indians and Their Music, ([Densmore 1926]), she briefly

discusses the question of finger hole position: “Indians in all

tribes questioned by the writer say that the finger holes in the

flute are spaced in a manner convenient to the player's hand.”

Sizes of flutes and material of construction may greatly vary

within one tribe,10 Many different kinds of wood are used,

including cedar, juniper, box-elder, reed and so on. Some less

common woods used are sunflower stalk ([Densmore 1923] 10 Ibid. ([Morris-F 1913]); also in many of the sources listed in bibliography. Color and design are among the visual aspects most revealing as to the connection between the flute and its symbolic role. A large number of flutes described or collected by ethnographers and ethnomusicologists were painted in a variety of colors. Some colors such as red, pink, black, yellow, and green are particularly widespread. Colors are applied to the flutes either by staining, or drawing specifically symbolic figurations such as arrowheads, zigzags (depicting lightning), the horned water serpent, and stars. Colors bear a wide and intricate variety of connotations. Each color may be linked with certain aspects of life and the universe. Every direction of the world, for example is depicted by colors. Some of the geometrical designs mentioned above are burnt into the wood so that the black designs stand out on the lighter color of the wood. Another widespread tradition is the ornamentation of flutes with animal effigies. A Papago flute in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art collection, terminates with a bird's beak. The courting flute of the Sioux bears a bird's head. The Big Twisted Flute of the Sioux is ornamented with the effigy of a horse and painted red at the interior of each orfice. An Oglala flute on display in the New York Metropolitan of Art is decorated with a carved rabbit. In the Heye Foundation's Museum of the American Indian in New York, Cheyenne and Winnebago flutes on display end in bird's heads. In the intricate American Indian culture animals symbolize certain aspects of life or attributes such as bravery, successful hunting, and wealth. It is therefore not surprising to find animal effigies carved or mounted on flutes. Other ornamental and ceremonial devices often used include beads, shells, feathers, glass, chips of metals or even the attachment of small medicine bundles. The foregoing discussion of the different elements which effect the construction and appearance of the flute supports the assumption that non-musical concepts greatly influence flute making. However, there is clear evidence that musical criteria also play an important role: 1) the analysis of flute songs which follows this chapter demonstrates that there is, generally speaking, a uniform system in the musical style including scales. This would probably not have existed had their construction been entirely based on non-musical considerations, 2) the strongest evidence proving that flute makers were concerned with the pitches produced by their instruments is the fact that on many flutes a tuning block was mounted to control intonation. Examples of such flutes are described (including photographs) in a catalogue by F. Morris ([Morris-F 1913]) listing the musical instruments housed in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. On p. 124–5, #579 is a Chippewa flute with a tuning block, #1976 is one of the Apache, and #3541 a Seneca flute. A number of flutes to which a tuning block is attached are on display in the Museum of the American Indian in New York. Flutes in that collection which have tuning blocks include those of the Blackfoot, Semiole and Winnebago. The Flute Songs of the American IndiansIntroductionObjectivesAmerican Indian musical style has been, for a relatively long time, subject to continuous study. Although the music of .a number of tribes has not yet been investigated, and that of others still needs to be approached in greater depth, studies by a large number of scholars have aided in clarifying characteristics of regional styles and of other classes of music as well such as peyote songs, gambling songs etc. After a thorough review of existing research materials it became clear that flute-lore and musical style, despite their uniqueness and significance in North American Indian culture, have, so far, been overlooked or ignored. Some scattered data or individual transcriptions of flute songs can be found occasionally in analyses and articles dealing with other subjects. However no study to speak of centers around flute music per se. It is thus the aim of this chapter to explore this important subject in order to extend knowledge of the American Indian culture. LimitationsOne of the greatest limitations posed on this study is the fact that flute-lore is almost totally extinct among North American Indians. Most of the ceremonies and rituals in which flute was used (both musically and symbolically), are not practiced today any more. Courting, for example, is done in more modern ways, and does not involve serenading on the flute as in the past. A number of young American Indians today, who are aware of the painful impoverishment and decline of North American Indian traditions and culture are making efforts to revive what can be salvaged from a rich cultural past. Among them are also American Indian flute players who compose flute songs according to what they consider to be the traditional style, or rescue melodies from “old-timers” who may still remember some songs. This study is based entirely on material gathered early in the 20th century, when flute-lore was still an integral part of a living culture. Even though this fact presents many advantages, it also creates some serious limitations. Very little is known about the circumstances in which the material was elicited, about methods of collecting and about the informants and songs, as most of the informants and/or researchers are now deceased. The available recordings of past fieldwork are accompanied by rather sketchy notes about the items above. It is also difficult to determine to what extent these songs are representative of the flute musical style of their tribes since only one flute player was normally recorded from each tribe. This further complicates the issue of scales and tuning since only one flute was used to represent each tribe, and there is possibility of intra-tribal variety. In conclusion, despite the limited scope of this study (ca. fifty songs) and the problems described above, this thesis can provide a basis for more extensive future study of North American Indian flute music. The songs analysed here, recorded in ten different tribes at different times, can presumably be considered as an adequate sampling of flute musical style. This collection consists of recordings done by various ethnomusicologists between the years 1905–1952 (a list of recording dates, collectors' and performers' names is given below). In the recordings a number of flute melodies were each preceded or followed by a vocal version of the same song, done by the same performer. In the analysis differences and similarities between the two forms of performance are illustrated.

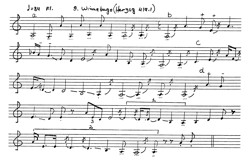

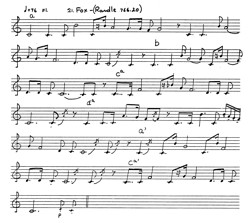

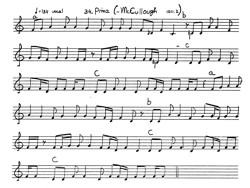

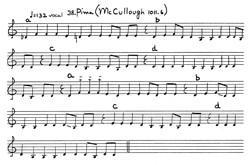

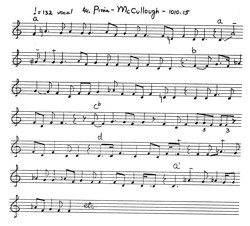

MethodsTranscriptions. An effort was made to transcribe each song in a manner closest to its actual sound. Barlines were not used, since the songs clearly exhibit the absence of regularly recurring accents. Time values represent as closely as possible the true length of each note, and were not modified to create a “normalized” transcription. Since all songs were characterized by a roughly regular pulse, tempo was determined by metronome marking. Tempo evaluation here does not attempt to explain or coincide with American Indian concepts of tempo, but was made for the purpose of comparison and analysis. For various technical reasons it was not possible to transcribe all songs beginning on a common tone. However a table of scales all transposed on C is provided in the back to facilitate comparison (see Figure 1). In this table, C is not to be understood as tonic but merely as the lowest tone of each scale (song), for not in all songs is the tonic identical with the lowest tone. Pitch Material. From each song all pitches were extracted and arranged in a row. A mode was determined through hierarchy of pitches (such a hierarchy was not assumed, but was actually found in all songs). The term, “scale,” is used here in its general meaning, namely, a group of tones arranged in order of pitch to a system of intervals. In each scale two or three “pillar tones” were identified according to role, frequency duration and place in the song. The tonic is defined as the chief gravitational point in the hierarchy. Other tones in the songs tend to flow and lead to repose at the tonic. The tonic often starts a song or phrases, it frequently ends phrases but always ends the song. At the end of phrases and of songs in particular, the tonic is generally repeated three to four times or appears in long time values. Besides the tonic, two other pillar tones usually exist in each song. They are here called the second and third pillar tone (the terms dominant and subdominant were purposely avoided because of their specialized implications). As in the case of the tonic, the second and third pillar tones as well were determined by role frequency duration and place. In the process of scale analysis no evidence was found that octave duplications are disregarded by the American Indian composers, so that in counting the number of tones comprising a scale these were not considered by the writer as one and the same. In North American Indian musical style one is obviously not dealing with music based on a theory of scales and intervals such as that of Western music. Each tone should therefore be regarded as part of the pitch material comprising the music. Furthermore, even in dealing with Western scales, octave duplication is never disregarded: analysis also reveals that tones an octave appart are not treated alike and there seem to be definite rules as to approaching each one and as to hierarcy among notes in a song. Phrases. In most songs, certain easily recognizable units were labeled as phrases. They were determined according to cadential patterns, phrase repetitions and general organization within each song. Phrases were marked alphabetically according to the following guidelines: 1. Intoning phrase (usually shorter than other phrases) three or more repetitions of the tonic, or three or more repetitions of tonic–octave–tonic. Such a phrase is marked “a.” 2. A phrase receives the same letter as another (e.g. a, a) if it is identical or exhibits only minor differences (no change in structural tones). 3. A phrase is labeled a' if the general skeleton (including structural tones) is the same as the phrase labeled “a.” 4. A phrase is labeled ba if it is different from the previous phrase, “a,” in structural tones, rhythm and final cadential pattern but contains a fragment clearly taken from phrases “a.” 5. Similarly to the above case, the phrase is marked ba8 if the fragment taken from a isa transposition from its original appearance an octave higher (ba8 same as before however fragment transposed an octave lower). 6. A phrase is marked b8 if it is identical with phrase, “b,” but transposed an octave higher (b8—same as above but transposed an octave lower). 7. A phrase is marked b'(+) when it is similar to a previous phrase, “b,” but is longer (b'(–) indicated shortening). The analysis and discussion in this thesis are based on detailed analysis resulting in statistical tables, which are presented on pages 91–129 in support of the discussion. Analysis

Pitch MaterialNumber of tones in the scale (Fig. 1, tables 1, 1a). The American Indians do not usually verbalize about their music to the point of creating an explicit theory. However, the aesthetic bounderies which they had come to recognize and accept reflect an existing system. In an attempt to analyze that system, care was taken to use those methods which were to lead to revelation of the principles behind that style. American Indian music was not conceived by its composers as based on scales. It seems to be founded on an entirely different set of principles, which will be clarified in the course of the analysis. Whereas extraction of pitches, and their arrangement into scales, enables the ethnomusicologist to unveil certain principles, at the same time such a method can also obscure and distort the analysis and result in false conclusions. In the following discussion dealing with the number of pitches used in the music, certain weakness and limitations of scale analysis will be taken in consideration and pointed out. When attempting to discover the “scale” of a given repertoire or song, one must differentiate between the collection of all pitches used and the core or “basic scale.” The difference in number of pitches between the two categories stems from the following: 1) Scalar Chromaticism resulting from changes in intonation in both flute and vocal melodies; 2) mistake and/or occasional deviation from the norm. Determination of the core of a scale poses a further problem, for it is often difficult to judge whether a tone is a deviation from the basic scale or one which is part and parcel of it even though it is used only once.1 The need of making such judgments inevitably leads to some imperfection. 1 In Western music too, a song may not necessarily use the entire range of the scale, or may use a tone only once, but would not, for this reason alone, be considered as based on a different scale.

Most of the songs in this collection are based on a fairly limited variety of pitches. All except nine songs use seven pitches or less (see tables 1, la). Many songs use as few as four to five tones. Two songs are based on an exceptionally large variety of pitches: Winnebago #1—utilizes nine different pitches, and Fox #20 has ten (both songs are vocal). The vocal songs in this study, all of which follow or precede flute renditions of the same song, tend to use a larger number of pitches than the same instrumental melodies, (e.g. #6–7; 12–13; 33–34; 35–36; 37–38). The reason lies in the fact that flute pitches are fixed by the physical structure of the instrument. Pitch flexibility is possible, to some extent, through varying the intensity of blowing,2 or by adjustments in the performer's lip or jaw positions. The singer however, is only limited at the extremes of his vocal range. Within that range his choice of pitch is theoretically unlimited from a continum of microtones. Since pitches within his vocal range are not organized by any physical restrictions, one finds in many of the vocal songs two and even three distinct variations on the same pitch, which in a transcription often translates into a greater number of tones. When the pitches used in a song are extracted and arranged in a scale, in some songs an almost chromatic scale results (e.g. #7; 13; 20; 29; 36; 38; 44). There is however no trace of chromaticism in the melodies themselves. As will be shown later, the use of semitones as melodic intervals is limited indeed. The selection of Pima songs (#33–44) clearly demonstrates the points made in the foregoing discussion. Most of eight flute renditions are based on four pitches and one song, on five. The four vocal versions of these songs use five, six and eight pitches. The scale drawn from vocal version #36 consists of eight pitches all spaced half steps apart. The melodic intervals actually used in the song are mostly major seconds and major thirds. In the middle of the second phrase of the song the singer had shifted to a higher pitch level; thus, the rest of the song was sung approximately half a tone higher. This resulted in a larger variety of pitches in the scale of the entire song, while the melody was merely the vocal version of the preceding flute rendition based on five tones. 2 By increasing the intensity of air flow, the pitch rises. Types of Intervals used in the Scales (tables 2, 2a, 3, 3a). Examination of scales shows that the most common intervals in the scales are major seconds and minor thirds respectively. Some scales contain more than one minor third (e.g. #2; 4; 8; 9; 10; 22; 25; 27; 29; 45). In the Pima songs the major third is used in the instrumental melodies instead of the minor third. The vocal versions, however, do use minor thirds where the instrumental used major thirds. Since songs of all other tribes examined, both vocal and instrumental, used minor thirds and the Pima instrumental melodies are an exception, one is led to conclude that the particular flute on which the Pima songs were played may have had a built-in irregularity which the performer was not able to correct. The same performer did sing a minor third in places in which he played as major third in the flute melodies.

Overall Scale Patterns (tables 3, 3a). The scales extracted from the songs exhibit two main types: 1) a scale system in which the interval between the first and second degrees in a third or occasionally a fourth, the rest of the intervals being mostly major seconds; 2) scales in Which the interval of the minor third lies in a different place in the scale, mostly between the second and third degrees, preceded and followed mostly by a major second. In others, the minor third is at the end, and is often the second minor third in the scale (e.g. 24; 27; 28; 29; 32). Examples of scales containing one minor third at the upper end of the scale: 17; 22; 45; 47; 48 etc. The differences between the two types of scales are clearly exhibited in the melodic patterns and cadences all of which will be discussed at a later stage of the study. To the first type belong ten out of the twelve Pima songs (33; 35; 37; 38; 39; 40; 41; 42; 43; 44), Kiowa 45; 47 (two out of three songs), Sioux 48 and Flathead #49. As discussed earlier, vocal versions of the songs often contain two or three variants of some pitches. If, in order to discover the underlying system, those closely clustered pitches are combined and viewed as one tone, more consistant scale patterns emerge revealing pentatonic formations. For example: #34 (Pima) is a vocal version of the instrumental song #33. In the vocal rendition the tones C and Db occur only once each at points in which the same melodic pattern used D consistantly thereafter. The basic scale, then, one which this melody is based is D F G A (or C Eb F G transposed on C), the four tone scale beginning with the leap of a third labeled above as scale type one. The same is true of #36, which theoretically uses nine pitches; however, the melody, if sung without changes in intonation, uses only fIve. Thus the core scale for this song is C E F# G# A (transposed on C). The second type of scale includes all of the flute and vocal melodies of the Northeast (Winnebago, Mesquaki, Chippewa and Fox) and the two songs from the Yuchi and Apache tribes. The scale structure of their flute songs is the most clear cut and consistant. The minor third is always between the second and third degrees (except in the two Chippewa songs). The rest of the intervals in the scale are usually major seconds. Both flute and vocal melodies from the Northeast demonstrate a pentatonic structure as the core of the tonal material. Tables 3, 3a illustrate that in the majority of the scales of these songs the lowest five tones follow a pentatonic pattern very common around the world, namely, C D F G A. Great variation exists in the number of tones and in intervalic relationships in the remaining tones in the scales, which constitute an extention of the basic five-tone system. This variation can already be detected in the intervals between the fourth and fifth degrees. Although the majority of intervals between these degrees is a major second (as expected in the above-mentioned pentatonic system) a significant number of scales deviate from the model and have other intervals (minor seconds, and occasionally even fourths). The deviation from this norm is particularly evident in the scales of the vocal melodies of the Northeastern and is, as mentioned before, perhaps due to greater flexibility in selection of pitch.

Mode (tables 4, 4a). In all of the melodies analysed a distinct hierarchy of pitch material is present. Usually three pillar tones act as gravitational centers to which other tones flow for temporary or final repose. Thus they are responsible for coherence and direction in the music. The tonic (T) has the strongest gravitational pull. As already stated, it often begins songs or phrases, ends phrases, and always ends the songs. Its frequency and duration also exceed that of the other tones. Two other secondary pillar tones (labeled 2, 3) usually exist in each song. (In songs using only four pitches there are usually only one or two pillar tones.) The secondary pillar tones may start or end phrases and also serve as points of temporary repose in the phrase. By creating a feeling of momentary repose they regulate the energy of tension and relaxation. They too are determined according to frequency and duration. Fig. 1 and tables 4 and 4a, demonstrate that in thirty seven out of forty nine songs the strongest gravitational point is the lowest tone of the scale. This includes the vocal and instrumental songs of the Winnebago, Mesquaki, Fox, Chippewa, Apache, Kiowa, Sioux and Flathead. The only group of songs in which the tonic is not the lowest note are the Pima songs. In all the Pima flute and vocal melodies the second degree of the scale constitutes the tonic. In two other Pima vocal songs the tonic is on the third and fourth degrees. In all of the Northeastern songs analysed, the second and third pillar tones appear to be consecutive and a fourth and fifth distant from the tonic (a discussion of the significance of these intervallic relationships is presented below—see section on skeletal structure). In the songs of the Northeast the secondary pillar tones usually fall on the third and fourth degrees. The two are interchangeable and can be found at an almost equal rate on either the third and fourth degrees. In contrast with the Northeastern songs, in other tribes a much less regular pattern of secondary pillar tones is evident. In the Pima flute renditions, for example, the second pillar tone is on the lowest degree of the scale preceding the tonic. In the vocal Pima melodies however, the second pillar tone precedes or follows the tonic and. in one case (the second vocal melody) the second pillar tone is on the fourth degree while the tonic is on the second degree. The only song of the Yuchi tribe, in this collection, is the most unusual in construction: its tonic is on the sixth degree, the last note of the scale. The second pillar tone is on the fourth (a third distant from the tonic). The third pillar tone is on the lowest tone and a fifth away from the second pillar tone. Many of the songs outside the Northeastern region do not seem to have a third pillar tone. Those songs in which a third pillar tone is employed it is usually located on the third degree. The majority of songs which do not make use of a third pillar tone are composed of only four or five pitches. Range of Scales (tables 5, 5a). The range of the scales (songs) is fairly wide with the exception of those of the Pima. Both vocal and flute melodies all but these extend between a seventh to an eleventh, with the majority occupying octaves and nineths. The range of the Pima songs is by far the most limited: the range is a fifth (diminished, augmented or perfect), and only one song occupies a major sixth.

Form (tables 6, 6a, 6b, 6c)Repetition of material heard earlier in the song is a vital feature in the compositional process of both vocal and instrumental melodies. The prevailing form is iterative, a form which often contains paired phrasing. Thirty two out of forty nine songs have an iterative form. When paired phrasing occurs, only one or two phrases are repeated (e.g. 5; 6; 11; 13; 24; 26; 34; 35). Some songs are composed of two or three phrases only, one or two of which are repeated several times in the song (e.g. 4; 33). The remaining seventeen songs which are not iterative are equally divided between reverting and progressive forms. The reverting form too, is based on the principle of repetition so that this procedure is of great importance in the compositional aesthetic of flute songs.

MelodyMelodic Intervals (tables 7, 7a). A close examination of the melodies reveals the use of only a limited variety of intervals throughout the repertoire. Primes, major seconds, minor thirds and fourths are employed almost exclusively. Octaves, fifths and major thirds are utilized to a much lesser degree, other intervals are very rare.

In the flute and vocal melodies of all tribes examined, the prime and major second are the most frequently used (each occupying about a third of the total number of intervals). In the songs of the Northeast, minor thirds and fourths are almost equally used and are second to primes and major seconds in frequency. Major thirds are very rarely used. In tribes outside the Northeast, thirds are employed more than twice as often as fourths. Major thirds occur frequently in the Pima flute renditions, while those of other tribes include only minor thirds. (As mentioned earlier the reason for this exception may be because of a built-in irregularity in the flute which the flutist cannot correct in performance.) The picture becomes more homogenous in the vocal renditions where all use minor thirds, including those from the Pima. The frequency of intervals larger than fourths drastically declines in all songs. Leaps of fifths are used much less often than fourths. For example in the vocal songs of the Northeast, 84 fourths are found but only 22 fifths. In the flute melodies of the same region 156 fourths occur, but only 34 fifths. Octave leaps are used rarely and leaps such as sixths and sevenths are even less common. An exceptional case is the Yuchi flute song #31 in which fourteen leaps of a seventh occur. A cardinal aspect of the style is the distribution of melodic intervals in the song. An examination of the melodies shows that even the few intervals which constitute the majority of melodic movement, are not evenly distributed throughout the songs. Primes are employed mainly at beginnings and endings of phrases. They usually occur in series of three, four or more in a row, in long time values, thereby creating a strong feeling of repose (e.g. #1; 3; 5; 7; 19; 20; 32). A considerable number of primes is scattered throughout the songs as well; however, they are of shorter duration (often eighth notes) and do not appear in chains of three of more as they do at beginnings and endings of phrases. They are thus not producing a static effect in the musical flow (e.g. 2; 4; 5; 6; 7). The use of octaves in particular is confined mostly to the opening portion of songs. There they appear in groups of two to four and act as an intoning unit. A few octave leaps can be found at the ends of phrases as well. In the Yuchi flute melody #33 mentioned above, the fourteen leaps of a seventh (an interval otherwise very rarely used in the rest of the repertoire) occurs at beginnings and particularly at endings of phrases. Since primes and octaves are by and large confined to beginnings and endings of phrases it becomes evident that the melodic movement is carried mostly by major seconds, minor thirds and fourths respectively. The almost total absence of minor seconds and major thirds as melodic intervals (with Pima flute renditions as an exception) supports the assumption that two pentatonic systems, namely C Eb F G A and C D F G A are the core of this style. Most of the melodic activity centers around the above tones and the relationships among them. Each of the performers usually did not use major thirds, even though they could have easily created them by “skipping a tone in the scale.” Instead they chose minor thirds almost exclusively, which constitutes the “gap” naturally present in both pentatonic constructions. Similar is the case of minor seconds which is not present in the above mentioned two types of pentatonic models.3 3 The subject of chromaticism was discussed earlier in the Pitch Materials section.

The Skeletal Structure of Songs (Fig. 2). The extraction of skeletal tones from the songs proves highly instructive in demonstrating the principles upon which the melodic forces in this repertoire operate. The majority of the songs are constructed of tetrachords and/or pentachords. A small number of phrases in some songs is built on trichords combined with tetrachords or pentachords. Each phrase is based upon tetrachords, pentachords or sometimes trichords. It usually involves a combination of at least two of the above. Among the chief structural techniques is the use of two disjunct tetrachords (a) (e.g. #2, third phrase; 5, second phrase; 6, first phrase; 7, second phrase; 9, fourth phrase; 20, third phrase).

A less common combination consists of two conjunct tetrachords (b), (e.g. #8, second phrase). Another common structure shows a tetrachord and a pentachord in a conjunct position (c). The tetrachord is usually above the pentachord (e.g. 20, second phrase; 15, fourth phrase; 2, fifth phrase; 3, second phrase). Occasionally however, the pentachord is positioned above the tetrachord (d), (e.g. 10, third phrase; 11 third phrase; 12 second phrase). A large number of phrases in the songs are composed of portions of the above formations, and often of a combination of two or more. For example, in #15, the second tetrachords are (from above) A–E and D–A. In the second phrase they are again found, but not in the usual order. A–E is established first, then the lower tetrachord D–E is interrupted by a return to E, so that the lower framing interval becomes a pentachord. In song #17 most of the first phrase centers around the bottom range. The upper tetrachord is briefly established (A E D E) and the rest of the phrase emphasizes the lower tetrachord D–A. In song #23 several phrases center mostly around the lower pentachord. The sixth phrase seems to combine a tetrachord C–F and a pentachord C–G. Other examples of varied combinations are all of #24; #1 third, fourth and sixth phrase; #7 second phrase; #9 fourth phrase. In a number of songs a different type of structural relationship at first seems to exist. Some structural tones relate to one another by thirds. In the Chippewa song #30 for example, the third pillar tone relates to the tonic (below) and second pillar tone (above it) in thirds. It seems justifiable to assume, however, that these relationships are no deviation from other phrases or songs. The above mentioned Chippewa melody is constructed on a pentachord which rests on the tonic and second pillar tone relationship. In the course of the melody this pentachord is clearly divided into two nuclei of thirds which reinforce and center around the upper, then the lower third of the pentachord. Also in many of the Pima melodies, phrases are based on relationships of thirds. Since the range of these songs is usually limited to a fifth, here too the pentachord is broken up into two, reinforcing each half of the architectural frame. In the Pima songs therefore, pillar tones tend to have a much less prominent role, while emphasis on the extreme fifth is the main concern. During the process of establishing the framing fifth each tone becomes a momentary center, is established, then abandoned in favor of another (e.g. #33 first, second, fifth and sixth phrases; #35, second, fourth and sixth phrases, #39, the first five phrases; #40 the first, second, sixth and seventh phrases; #41 first three phrases and the sixth and seventh as well) . From earlier discussions, and on the basis of the information in tables 4, 4a, 7, 7a, and Fig. 2, one may postulate that the underlying principles of the architecture of the flute music style analyzed (including the vocal renditions), are founded upon relationships of fourths and fifths. Within frames of tones separated by fourths and fifths other intervals, mostly smaller ones, fill in or circumvent these structures. Reinforced by rhythmic patterns these intervals serve as the dynamic force carrying on the movement. All of the above becomes evident from the evaluation of the place of pillar tones, the use of melodic intervals; the skeletal layout of each song and lastly, the extraction of pitch material to form scales. The music is based on the interaction between two forces: 1) the constructive intervals (fourths and fifths) which create stability and goals, 2) content intervals (primes, seconds and thirds) which are responsible for the lacing-in of the melodic movement. The two forces balance one another in the constant play of movement and repose, tension and relaxation. Cadences (tables 8, 8a, 9, 9a). All songs examined for the purpose of this study exhibit the use of cadential patterns at the end of phrases and songs. Several types of cadences dominate the entire repertoire. One may distinguish Final cadences from Non-Final cadences. Among the final cadences two main formations are common: descending and undulating.