|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Instrumental and Vocal Love Songs of the North American Indians

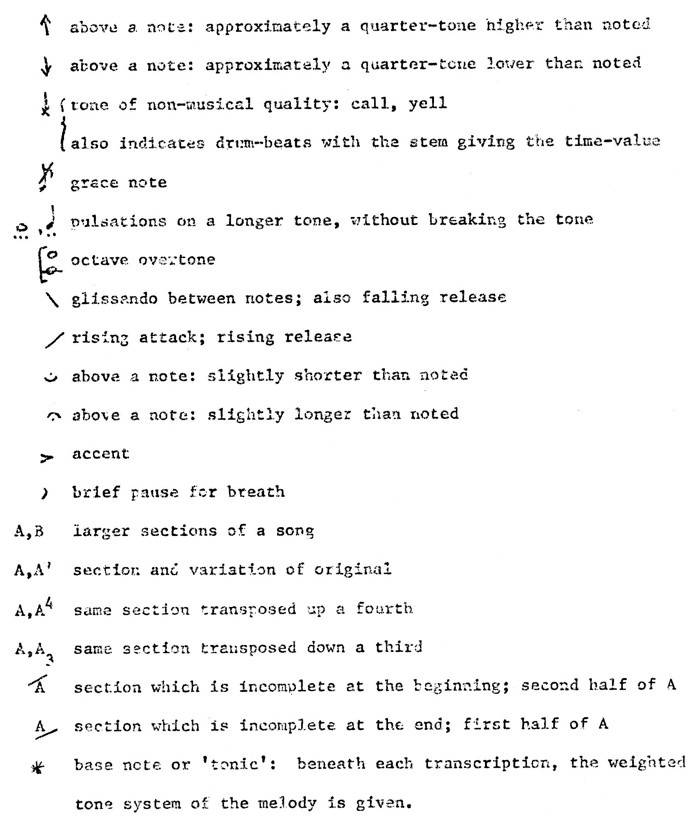

AcknowledgmentI wish to thank my advisor, Professor David P. McAllester, for his encouragement and constructive criticism during the writing of this thesis. IntroductionThis study of instrumental and vocal love songs has evolved from and will attempt to continue the research begun in two articles, “Special Song Types in North American Indian Music” by George Herzog ([Herzog 1935a]) and “Musical Areas in Aboriginal North America” by Helen Roberts ([Roberts-HH 1936]), both written more than forty years ago. The Roberts paper, which in part delineated musical areas by means of the distribution of instruments, clearly pointed out the lack of any information concerning the music of melody-producing instruments in aboriginal North America. While so much can be said of musical instruments, almost nothing is known of the music which might have been produced by those capable of more than one tone. As far as my research indicates, no thorough discussion of the flageolet, which was used almost exclusively as a courting instrument, exists in the relevant literature, with the exception of Merriam's treatment of the flageolet among the Flathead Indians. Accordingly, the first chapter of this paper will consist of a study of the courting flute: its construction, distribution, the beliefs and behavior associated with its acquisition, and its social function will be discussed in detail. The second and major section of this thesis will deal with the melodies played on the courting flute and with the closely related genre of love songs. Together they contribute a special class of North American Indian music. These songs and flute melodies have never been taken together as a group and studied for their stylistic unity. Very frequently found in the same geographical location, flute melodies and love songs had a fairly wide distribution north of Mexico, being most highly concentrated through the central U.S.A. in roughly the Plains–Plateau–Southwest areas. Since this music cuts across several musical areas, can it be shown to possess a homogeniety within itself and a consequent dissimilarity to the other music of its area? This was the fundamental question posed by Herzog in 1935. To attempt an answer, flute melodies and love songs from tribes located in four musical areas, the Western Great Lakes, Plains, Plateau, and Southwest will be analyzed, studies, and finally compared with the general stylistic traits of the music of each area. Chapter 1 — The Courting Flute1.1 — Terminology and ConstructionThroughout the literature disccusing Native American wind instruments, the terms most frequently used are whistle, whistle flute, flageolet, open flute (vertical and transverse), and single and double reed pipe. Although the distinction between instruments using reeds as the vibrating mechanism and those without reeds is clear, the other terms are often confused. The instrument under discussion here is correctly called a flageolet and belongs to the group of instruments known as whistle flutes ([Apel 1970], page 925). By way of illustration, the European flageolet and recorder are also whistle flutes. These two instruments are distinguished from each other by the number of finger-holes, six and eight respectively, and by their positioning ([Bessaraboff 1941], pages 62–63). The functioning principle, however, is the same. In all whistle flutes the upper end of the instrument is stopped by a plug or fipple with only a narrow slit, called a flue, remaining. The breath is led through the flue toward the sharp edge of a small opening below the fipple. The Indian flageolet is a slight variation on this design in that the narrow air channel is formed outside the cylinder, thus requiring the addition of the characteristic wooden block, or “saddle.” The materials and method of construction fo the flageolet were remarkably similar througout North America. Red cedar was the most commonly used wood, although other stright-grained woods such as box-elder, ash, sumac, elderberry, redwood, osage orange, and fir are also mentioned in the literature as being suitable materials. More recently flageolets have been made from metal gun barrels and nickel tubing. Features of these metal flutes, such as tone quality and pitch level, which differ markedly from that of a woode flute will be discussed in the following chapter, “Instrumental Love Songs.”

The instruments were generally about 1½ inches in diameter and

20 to 21 inches long; however, they could vary in length from

11 inches (Northern Ute / [Densmore 1922], page 23)

to 24½ inches (Omaha / [Fletcher 1893], page 72).

Densmore has stated that the length of the instrument wad determined by the stature of the player; for example,

the distance from the inside of his elbow to the end of the middle

finger ([Densmore 1926], page 95) or the length given by “spreads” of his hand

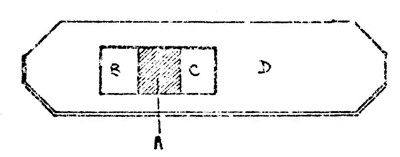

([Densmore 1929b] To make a flageolet a straight section of wood was split lengthwise and the insides of each half were hollowed out to form a cylindrical bore. A block (A) — see figure 1 — was left inside the cylinder creating a solid unbroken partition between the upper and lower chambers. The chamber containing the mouth-end was proportionally shorter (1:3) than the body of the instrument. Small square holes (B and C) were cut into each chamber just above and below the partition. The surface around these holes was then made smooth and flat and a thin wooden or metal plate (D) laid over it. This plate had a rectangular hole cut into it which fit exactly over the two holes in the cylinder (Figure 2). Finally, a wooden block (E), flat on the underside and carved according to the maker's fancy or tradition on top, was tied or glued over this plate. Air blown into the end of the shorter chamber flattens into a thin stream as it passes between the partition and the plate. At the entrance to the longer chamber the airstream impinges on the sharp edge or “lip” of the plate and sets the column of air in vibration. At this point the airstream divides. To allow surplus air to escape, the block is either positioned to leave the second hole partially uncovered or has a vertical groove carved into it.

The mouth-end was either blunt, tapered to an opening smaller

than that of the tube, or shaped into a small tube which projected

from the instrument to form a true mouth-piece. The flageolet had

four to eight finger holes ([Baker 1882]

(the tone system for every flageolet melody discussed in this paper is given at the bottom of each transcription, see pages 45–72 of the PDF version of this thesis).

In addition to the finger-holes that were stopped, the flageolet

of the Flathead Indians had a seventh hole placed near the

bottom of the instrument. Although it was never covered, the instrument

was considered incomplete without it

([Merriam-AP 1967], page 50). The Omaha,

Onondaga, and Chippwea flageolets are similar in this respect since

they all feature four small holes arranged circularly near the bottom

end. Baker's drawing ([Baker 1882]

1.2 — DistributionThe flageolet had a fairly wide distribution north of Mexico but was most highly concentrated through the central U.S.A., in roughly the Plains–Plateau–Southwest area. An early distributional map by Helen Roberts ([Roberts-HH 1936], page 17) shows that the flageolet existed in an area extending from the Western Great Lakes to the lower Mississippi and west to the Colorado River. Two other locations are also maked: California, where only the Mojave knew the flageolet ([Kroeber 1965], page 22), and the Southeast. The Roberts map corresponds closely with an earlier listing by Curt Sachs, given below ([Sachs 1929], page 214) of the Indian groups who possessed the flageolet. (The figures in brackets indicate the number of finger-holes of the various flageolets).

1 Also known as Chippewa. The inclusion of Altmexiko (pre-Columbian Mexico) in this list should be noted since it has been suggested ([Galpin 1903], page 135; [Sachs 1929], page 214; [Roberts-HH 1936], pages 20 & 25) that the flageolet originated in Mexico and subsequently spread northward.2 2 The flutes generally were known to the Indians of the Southwest in the prehistcric period has been verified by several excavations. Both a painted pottery plate from the Hohokam civilization ca. 8OO A.D. found at Snaketown, Arizona ([Collaer 1968], pages 48–49) and a pictograph ca. 700–900 A.D. in the Hagoe Canyon in northeast Arizona ([Brown 1967], page 83) portray stylized flute-players blowing long, end-blown flutes. Another archeological find in the Prayer Rock Valley, northeast Arizona has proven the existence of open, end-blown flutes in the area ca. 620–670 A.D. ([Bakkegard 1961], pages 184–186). A search to augment these early distributional listings has revealed the existence of the flageolet among these additional tribes (see distributional map, Figure 6):

1.3 — FunctionIn the summer of the olden time there might often be heard at eventide the call of flutes. It was the youths upon the hill-side piping love-songs. Every one may know a love-song when he hears it, for the flute-tones are long and languorous, and are filled with a soft tremor. When a maiden heard the flute-music of her lover without, she always found it necessary to leave the tipi to draw water or to visit some neighbor.

Although occasional reference is made to the use of the flageolet in ceremonies

([Radin 1923], page 123)

and as a warning or war signal

([Densmore 1929b] Because of its function, the flageolet was considered the personal property of the player and was rarely borrowed or loaned. Flageolet songs appear to have been individual creations and were, therefore, also personally owned. Something of the supernatural was often attached to songs played on the flageolet. In Menominee tradition it is said that a man who played the flageolet carried “love medicine” with him, an indication that songs possessed magical qualities ([Densmore 1932a], page 208). Among the Flathead Indians, Merriam discusses the relationship of a guardian spirit in association with flageolet melodies. The flageolet was usually made on the instruction of the spirit, who also gave the man the songs. When a song was played, it was not even necessary that the woman to whom the song was directed be able to hear it. “A woman always knows when someone is singing a love song to her. It is like a dream. The spirit that gave the man the song would be the one who caused her to know.” ([Merriam-AP 1967], page 60). As with the Flathead, intervention by the supernatural also occurred among the Crow Indians, where flageolets were often given to suitors in a vision. A supernatural being, usually in the form of an elk, would appear playing a flute and his music would cause all the female animals to run towards him. After such a vision the would-be suitor returned to camp and, taking his example from the elk, would make an exact copy of the kind of flute that had been revealed to him. With this flute he would be able to irresistably charm the woman he desired ([Lowie 1935], page 52) A more elaborate version of the origin of the courting flute is still current in Plains Indian mythology. I Richard Erdoes' collection of Indian legends ([Erdoes 1976]), Henry Crow Dog, a Sioux from Rosebud, South Dakota, describes the creation of the first “Siyotanka.” When the young hunter awoke, the sun was already high, and on a branch of the tree agains which he was leaning was a red-headed woodpecker. The bird flew away to another tree and then to another, but never very far, looking all the time over its shoulder at the young man as if to say “Come on!” Then, once more the hunter heard that wonderful song, and his heart yearned to find the singer. The bird flew toward the sound, leading the young man, its flaming red top flitting through the leaves, making it easy to follow. At last the bird alighted on a cedar tree and began tapping and hammering on a dead branch, making a noise like the fast beating of a small drum. Suddenly there was a gust of wind, and again the hunter heard that beautiful sound right close by and above him. 3 This account of the method of construction is unique. As described earlier, all other sources indicate that the wood was split lengthwise and hollowed out to form a cylindrical bore. It is hard to imagine a bow-drill being able to make as large and as long a bore as is required.

Other origin myths have also been document. According to Mandan

legend the flageolet was created by the Old Woman Who Never Dies by

taking a long section of a large sunflower stalk, hollowing out its

length, and cutting seven holes into its side. Each of the seven

holes represented one month of winter and upon playing the instrument,

snow would fall.

([Densmore 1923] To conclude this chapter on the courting flute, an interesting and informative summary is provided by Belo Cozad, a Kiowa Indian who was recorded by Willard Rhodes in the late 1940's. On this recording, Cozad prefaces his performance of a Kiowa melody (14; see transcription) with a short personal biography and his version of the “story” of the Kiowa flute. The passage which follows is of particular interest for the first-hand information it contains about the source of his flute musich, its value and importance. I'm a Kiowa tribe; my daddy he's the chief of the Apache Indian. He's hte first one who went to Washington city to see the Uncle Sam. A lot of Kiowas went with him, and they all die out. I'm seventy-seven years old now. I'm pretty old. And I like to give you some kind of new about this music — music I got, you know. If you'd like it I'll go and fetch it for your, sing for you and you can have that long as you live. And remember me and tell all your friends that you saw me right here at this Riverside Indian School. I like to play music for you and put some good songs that I know — I made it myself, good songs … for you and keep it as long as you live. I got this music from way back in Montana. One of a … poor boy, he's got no home and he went up on the mountain and stayed four nights there and he learned this music. He got it from some kind of spirit, he give it to him, show him to make it this way and to make it good music. And keep it as long as you live and you make it your good living because these trees … good trees, called cedar tree … It's a great tree, you know. And that's where he got this … From now on he's got this music and he's coming to well-off. He's got well-off womans and good home … raised children … I'm going to play it for you so I want you to hear good. (From Folk Music of the U.S. from the Archive of Folk Song, S I, b 10). Clearly, the value and importance of music is foremost in the speaker's mind. He offers to play his music for his audience so that they may have it as long as they live. Power is attributed to good music and he makes a direct connection between it and economic success: “from now on he's got this music and he's coming to well-off.” The story of his music's source substantiates the claim that, among Plains Indians, flute music is often received in a vision: “he went up on the mountain and stayed four nights there and he learned this music. He got it from some kind of spirit, he give it to him, show him to make it this way and to make it good music.” Towards the end of his story, the speaker expresses his sense of a connection between the cedar tree, from which the flute is made, and a successful life: …you make it your good living because these trees … good trees, called cedar tree … This statement suggests that, to the Indian mind, the combination of the cedar tree, symbol of the powerful force of Nature, and music, which derives from supernatural sources and is also imbued with power, guarantees the success of any person who possesses flute music. The speaker does not identify the song he plays nor does he describe the courtship function of flute music. However, this piece is very similar to the Kiowa flageolet melody (16) which appears on Side II of American Indian Soudchief Recording 248 under the title “Kiowa Indian Love Call.” [[Cozad-E 1964]] Chapter 2 — Instrumental Love SongsAmong all recordings of American Indian music that have been published, only a small proportion is of flute songs. This is no to suggest, however, that the genre has been overlooked or neglected but rather that few flute melodies exist. As Nettl points out, “a typical tribal repertory may consist of several hundred vocal songs and a dozen flute melodies.” ([Nettl 1954], page 7) Although Nettl does not name the tribes upon whose music he bases this statement, it has been shown in the case of the Flathead Indians ([Merriam-AP 1967]) to be a fairly accurate estimate. For this study, nineteen recorded examples of flute melodies from the Plains–Plateau–Southwest are are available and these have been transcribed to permit detailed comparison.1 Most of these recordings have been issued by Ethnic Folkways and the Library of Congress.2

1 In addition to this music, a Nez Perce flageolet melody published

in Curtis, Edward S., The North American Indian, vol. 8, page 50; one additional

Flathead melody from Merriam, Alan P., Ethnomusicology of the Flathead Indians,

page 182; two Menominee melodies from Densmore,

Frances, Menominee Music, pages 208–209; and three Omaha pieces, two from

Fletcher, Alice C. A Study of Omaha Indian Music, page 151, and one

from Fletcher, The Omaha Tribe, page 319, were also examined. From the list which follows, it can be seen that flute music from the Central Plains has the best representation, while melodies from groups on the periphery of the Plains area, for example, the Chippewa and the Apache, are few. No recording of flute music from the extreme Northeast (Iroquois) or Southeast (Alabama, Yuchi, etc.) were found.

Although this list may reflect an impalance in available recordings, the predominance of Plains melodies is not unexpected since the practice of serenading with the flute appears to have been strongest in the Central Plains and references in the literature to this tradition are more numerous than for any other area. In order to discuss regional differences, the flute melodies will be divided according to musical areas. It should be rememberd, however, that in dealing with music that is played on an instrument of fairly uniform design in all regions except the Southwest, it is to be expected that features such as range and tone system will conform to a standard pattern. Others such as performance style and ornamentation may be more variable but, nevertheless, will reflect an instrumental idiom. 2.1 — Western Great Lakes / PlainsThe Western Great Lakes area, in which the Chippewa, Winnebago, Meskwaki, and Menominee are located, lies on the edges of both the Eastern Woodlands and the extreme northeastern Plains. Both Roberts ([Roberts-HH 1936], page 35) and Nettl ([Nettl 1954], pages 24–25) place this region within the Plains musical style. Of the nine flute melodies which have been studied for this area, all but the Chippewa piece present a remarkably homogeneous pattern. The range of all the pieces lised between 12 and 14 semitones; i.e., a semitone below and above the full octave. Scales are most often pentatonic (anhemitonic) (3, 4, 7, D2) and hexatonic (5, 6, D1).3 One Menominee piece (2) is built on only four tones; while the Chippewa is based on seven tones without the octave repeitition. Both range and scale are sonsistent with the types of melodies that can be produced from the six-holed flageolet common to this area. The range, however, is smaller than would normally be found in the vocal music. According to Nettl's survey, “the range of most of the Chippewa and Menomini songs is very large; the average is the largest in North America. Of the Chippewa songs, only 9 per cent have a range smaller than an octave and 36 per cent greater than a perfect eleventh. The Menomini ranges are only slightly smaller.” ([Nettl 1954], page 25) 3 The melodies under discussion will be referred to by number. the two Densmore examples (Menominee) are designated D1 and D2. Transcriptions are given on pages 45–72 of the PDF version of this thesis. A consideration of melodic movement reveals another major difference between the instrumental and vocal music of the area In this eastern sub-section of the Plains, melodic movement is almost exclusively of the ‘terrace’ type ([Nettl 1954], page 25), to which none of the examples of flute music conforms. In contrast, all pieces (exclusing the Chippewa) show an initial leap of an octave to the highest tone and a gradual descent, occasionally only half-way, but most ogten through the full octave to the base tone.4 Instead of returning to the point midway in the melodic line, as would occur in the ‘terrace’ pattern, almost all subsequent phrases return to this same high note and repeat the descent. Again the reason for the difference between instrumental style and the typical vocal style may lie with the flute itself. Naturally if the instrument affords a range of only one octave, instead of the one and a half or some sometimes two of the vocal range, the descending line would be greatly limited by repetitions starting at consecutively lower points. The Chippewa melody, anomalous in other respects as well, has an undulating contour which is more typical of the Eastern Woodlands style.

4 In discussing melodic line and contour, some generalizations are

made for the sake of clairty. For example, if a phrase is said to

descend from highest to lowest tone it sometimes does not do this directly

as

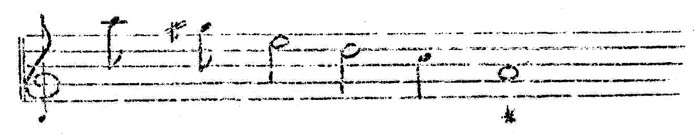

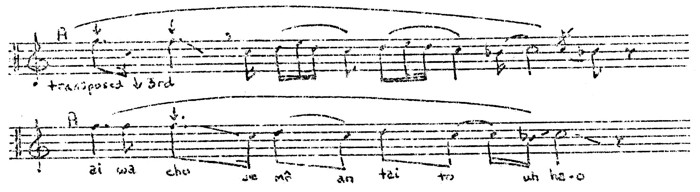

The intervals used in these melodies reflect an instrumental style. A typical beginning consists of an octave rise (the Chippewa piece begins with the interval of a perfect fifth) followed by large intervals of fourths and fifths. The latter parts of phrases have somewhat less movement and generally show a step-wise descent. (For example, see Figure 1)

The frequent use of wide intervallic leaps in combination with long-held tones at phrase-ends produces a quality of “spaciousness” ([Herzog 1935a], page 29), which is typical of both instrumental and vocal love songs. Again, the Chippewa melody is atypical in that the melody line is smooth, with step-wise movement predominating. Major seconds and minor thirds are common.

The rhythm of these flute melodies is free. Combined with

irregular melodic lines often containing wide intervals, a free

rhythm gives this music a rhapsodic quality. The tempo is relatively slow

(M.M.

In contrast to these melodies with a free rhythm and lack of consistent

meter, the Chippewa piece has a regular rhythm and underlying triple

meter. It uses only two rhythmic figures,

In recording a Chippewa song from an old Indian the writer found the rhythm peculiar, with frequent changes of measure lengths; later the same song was recorded by a young man, said to be an excellent singer. On comparing the phonographic records it was found that the younger singer had slightly changed the rhythm so as to avoid the irregularity in the measure lengths. The song had lost its native character and also its musical interest. ([Densmore 1918], page 59) If one considers the Chippewa melody to be a more modern peice, then not only the rhythm but other dissimilarities can be explained. Either it is a new piece, strongly affected by European musical style, or it is an older melody whose ‘native character’ has been gradually lost until it now resembles a European folk melody. In more typical melodies (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7), the ‘rubato’ tempo is in part aided by a wide distribution of durational values. All pieces except the Chippewa contain note-values from a sixteenth, or even thirty-second, to very long-held notes used at phrase-endings. Characteristic of neither Plains nor Eastern Woodlands musical style, this feature can be considered as idiomatic of the flute. Flute melodies from the Western Great Lakes area exhibit a definite binary structure (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). For example, the Meskwaki melody (7) which is fairly long and made up of many repeated phrases (iterative) has an exact repetition of material: ABBBA'B'B / ABBBA'B'B. Other forms are more progressive (i.e., contain new material in each phrase), as ABC / A'B'C (4) or ABC / DB'BC (6), but still show a division into two equal parts. Major sections of a piece are very clearly marked off by long-held notes, invariably the base tone or ‘tonic.’ These notes, which are one of the most characteristic features of flute music, function as short introductions, mark the ends of phrases and of major sections, and provide coda-like endings. In all instances this tone is the tonic or base tone. Other tones which are secondary to the base tone but still very prominent are the fourth, fifth, and octave above this note. An example of this weighting can be seen in the tone system of Winnebago melody (4).

Finally, there are a number of other features which, together

with the above, create an idiomatic flute style. The most characteristic

of these is the intense vibrato with which the tonic of the melody is

played. This apparently is essential to a good flute technique.

According to Fletcher

([Fletcher 1911] To be acceptable, a flute must give forth a full vibrating tone when blown with all six holes closed. It was interesting to watch men, old and young, take up a flute to test it; they would readjust the stop piece, bound to the top over the opening and usually carved, and if after several trials the instrument could not be made to give this vibratory tone the flute would be laid aside and no words would avail to make the man take it up and play a tune on it. Although speaking here of the Omaha tribe, the same prominence of a full vibrato on the tonic is seen in the flute music of the Western Great Lakes area. In this sampling, two of the pieces (4, 5) are played on flutes made form metal gun barrels. Both are able to produce a vibrato on their lowest tones, but in their higher range they are somewhat shriller. In addition, their base tones are slightly higher than those of the wooden flutes (i.e. b' and c'' instead of g' and a'). Because the base tone is played with such intensity, the octave above is often heard, either as an overtone or as a quick grace note. This appears to be a cultuvated effect, rather than accidental, since all pieces with the exception of the Chippewa contain many examples of it. Other grace notes within the melodic line are common (4, 5) as are downward glissandi, or falling releases (2, 4, 5, 6), rising releases (2, 3) and trilling (7). All of these ornamental devices occur to some extent in all pieces (again, except the Chippewa). 2.2 — Central PlainsTwelve melodies from the Sioux, Kiowa, and Omaha provide the material for studying the flute music of the Central Plains.5 As in the preceding group of melodies fromt he Western Great Lakes, the music is generally consistent within itself; i.e., many features are common to all pieces, with the exception of the two Sioux examples (8, 9). Through the following discussion it will become evident that the Sioux melodies should probably be considered, like the Chippewa melody, as newer pieces strongly influenced by European musical style. 5 Three of these melodies, designated F1, F2, and F3, are Omaha flageolet pieces taken from Fletcher, The Omaha Tribe, page 319, and Fletcher, A Study of Omaha Indian Music, page 151. See transcriptions, pages 65–67 of the PDF version of this thesis. Whether traditional or modern, all the melodies are within the range of 13 to 15 semitones; i.e., an octave to a major ninth. Flutes on the Central Plains almost always had six finger-holes, although the Sioux also made instruments with only five stops. While capable of a slightly fuller scale, the majority of flute melodies are pentatonic (8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16). One Kiowa piece (15) is hexatonic, and the remaining Sioux melody (9) is tetratonic. THis predominance of the pentatonic scale conforms with Nettl's findings for vocal music in the central and southern Plains ([Nettl 1954], pages 27 & 29). One peculiarity of scale was noted for a set of three Omaha melodies (10, 11, 12) which are all played by the same performer on the same instrument. In this music, the base tone is g', while the only ton consistently heard as its octave is g#''. This is the only occurence in all of the flute melodies of an augmented octave. Since, on these instruements, the upper octave is reached by over-blowing which has a natural tendency towards sharpening, the augmented octave is probably only a result of this. If, in fact, the g#'' were to have its own stop, this would be a very rare example of a tuning in semitones of the flageolet's lower range. In common with flute music of the Western Great Lakes, that of the central Plains also fails to show a ‘terrace-type’ of melodic movement. This presents a significant departure from Plains vocal style, where melodic contours are almost entirely of this type. Three Plains flute melodies have the same kind of melodic pattern as seen in the Western Great Lakes area; i.e., an initial rise of an octave to the highest tone followed by a gradual descent to the tonic (12, 15, F1). Kiowa melody No. 15 exhibits a tightly constructed version of this general contour. It has some resemblance to the ‘terrace-type’ movement but does not adhere strictly to its pattern. After the initial rise to its highest tone, the melody descends through a perfect fifth, returns, and repeats this first phrase. After reaching the halfway point a second time, the melody continues its descent to the base tone. This half also is repeated, thereby completing the symmetry. Shown diagrammatically, the melodic contour would be:

The majority of the flute pieces, however have a simple arch-form (8, 10), a combination of arch-form and straight descent (13, 14, 16, F2, F3), or an undulating (9, 11) melodic contour. In the combined form, the melody begins fairly low on its scale and gradually rises until the highest tone is reached approximately midway in the piece. Once the highest point is reached, the melody gradually descends through the full octave to the base tone. Two general patterns for the use of intervals in Plains music emerge. Half of the melodies (8, 11, 13, 16, F2, F3) consistently use small intervals of seconds and thirds, a feature which coincides with the general trend of Plains vocal music ([Nettl 1954], page 29). The other half (9, 10, 12, 14, 15, F1) makes use of wide leaps of octaves, fourths, and fifths, and represents a more idiomatic flute style. Of these, Nos. 9, 12, 14, 15, and F1 show similarity to the typical Western Great Lakes melodic movement: i.e., large intervals occur in the early parts of phrases, while the latter parts have somewhat less movement and show a step-wise descent. In general, a descending melodic line will contain wider intervals of fourths and fifths, while an arch-form or undulating line will have a predominantly step-wise movement.

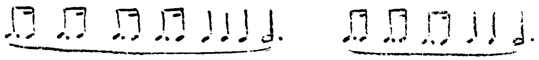

The rhythm of Plains flute melodies, in contrast to those of the

Western Great Lakes, is more restrained and regular. Several rhythmic

figures recur, giving these pieces a rhythmic unity which was not

apparent in the Western Great Lakes music. For example, the figures

In summary, Plains flute music presents a wide range of rhythmic possibilities from very free (14, 16) to strictly metrical (8, 9). In his study, Nettl found the rhythm of Plains vocal music similarly complex ([Nettl 1954], page 29).

As expected, the distribution of durational values is wide in

those melodies which are rhythmically free. Those with recurring

rhythmic figures (9, 11, 12, 13, 15, F2) show less of a distribution, while

the completely regular melodies (8, 9) are restricted to only two or

three note values. The tempo of all these flute melodies is generally

‘andante.’ (M.M.

Like Western Great Lakes flute music, the majority of Plains melodies have a binary structure (8, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16) which is clearly demarcated by long-held tonic notes. Again, this pulsating base note also functions as an introduction, which can sometimes be rather prolonged as in the Kiowa melodies 14 and 16. It also signals the end of a piece in all cases except the two Sioux melodies (8, 9) where an unusual coda consisting of two overblown notes not found in the body of the piece is heard.

These codas can probably be considered as a characteristic manner of closing for Sioux love songs. Sung versions of this type of ending occur in several of the vocal love songs and will be discussed more fully in the following chapter. Internally, the structure of Plains flute melodies is most often reverting (8, 10, 13, 14, 16) and only occasionally progressive (9, 10) or iterative (12, 15).6 This breakdown agrees with Nettl's findings for vocal music of the southern Plains where “reverting forms consisting of a number of short sections … account for almost half of the songs.” ([Nettl 1954], page 28). Elsewhere on the Plains, however, the most common form is an incomplete repetition which is not seen in these flute melodies. 6 Reverting: restatment of earlier material; progressive: no material repeated; iterative: repitition of material immediately preceding. (From Nettl, North American Indian Musical Styles, page 6). As in Western Great Lakes flute music, the tonic of a piece is always the lowest tone and is also the most prominent by virtue of its position at the beginnings and endings of pieces and usually at phrase endings as well. The only exception to this is seen in Sioux melody no. 8. Here the fifth below the tonic is the most prominent. A review of the tone systems of these melodies, which give the relative weightings of each tone in a given scale, shows that the fourth, fifth, and octave above the base tone are also structurally important. No additional ornamental devices are seen in Plains flute music that were not used in the Western Great Lakes area, although the style of playing in the Omaha melodies is relatively more staccato. Omaha melody no. 13 is also remarkable for the heavy ornamentation centering around the long-held tonic notes. In addition to the usual overblow octave grace notes, rather elaborate turns precede these notes in several places.

2.3 — PlateauIt has been hypothesized that the flageolet originated in Mexico and subsequently spread northward ([Galpin 1903], page 135; [Sachs 1929], page 214; [Roberts-HH 1936], pages 20 & 25). Roberts pictures the diffusion of Mexican influences into the continental U. S. A. as having fanned out somewhat in the shape of a mushroom — strongest in the central corridor of the southern and central Plains and less prominent in regions to the north, northwest, and northeast. Therefore, in moving away from the central Plains and into the Plateau area it is not unexpected to find few references to the courting flute and even fewer examples of its music. Only four examples of flageolet melodies are available for study: three from the Flathead and one from the Nez Perce Indians.7 Withing this small sampling, however, the melodies are similar in several respects. 7 Two Flathead melodies (17, 18) have been transcribed from Alan P. Merriam's recordings, Songs and Dances of the Flathead Indians; the third piece (M1) appears on page 182 of his Ethnomusicology of the Flathead Indians and C1 is a Nez Perce melody taken from Curtis, The North American Indian, volume 8, page 50.

The range of these melodies varies from 12 semitones (G1) to

15 semitones (17). ALl of the Flathead melodies are based on pentatonic

scales (anhemitonic), while the Nez Perce melody is heptatonic

(d', e', f#', g#', a', b', c#''). Curtis' description of the Nez Perce

instrument as a seven-holed flute made from an elderberry stalk

([Curtis-E 1911c] In melodic movement the four Plateau pieces are quite divergent. Only one (17) shows the strongly descending pattern typical of Plains and Western Great Lakes melodies. The remaining three have an undulating movement (M1, C1) or are arch-form (18). The intervals used in all four melodies are small. Step-wise movement predomintes, with some use of falling thirds (18, C1) and fourths (17, M1). These usually occur at phrase-endings. The pieces are all played with a free rhythm and the distribution of durational values is fairly wide in all except No. 17. This Flathead piece presents a pattern of greater rhythmic stability than the other through its use of only three durational values, eighth, quarter, and half, and notes of the same duration often follow consecutively.

Phrase patterns tend to show incomplete repetition and are non-symmetrical (No. 18: ABA / BA' ; C1: AB / B ; and M1: ABB). Only no. 17 is binary and iterative (AA' / AA'). In these melodies, unlike the majority of Plains and Western Great Lakes pieces, there is no long-held base note to provide a distinct introduction, mid-section, or ending. No. 17 approaches this form somewhat with held notes at phrase endings but these are not on the tonic. In fact, in all pieces except M1 the tonic does not have greatest prominence, which is a major difference between flute music from the Plateau area and that of the Plains and Western Great Lakes. The performance style of flageolet music in the Plateau area is generally rather subdued in comparison to that of the Plains. For example, neither long-held notes played with an intense vibrato nor overblown octave grace notes are heard. Some rising releases (18) and falling glissandi (M1) occur at phrase endings, and grace notes, typical of the instrumental style, are common (17, 18, M1). Two of the Flathead melodies are played on flageolets made of nickel tubing. These instruments produce a tone which is thin and light but without shrillness. Only the Nez Perce melody has the full tone and spacious quality typical of Plains flute music. 2.4 — SouthWest

In the Southwest, the Apache appears to be the only group to use

the courting flute, and this area was found to have very little flute

music. The only example of Apache flute music available for this

study is taken from the recording, Music of the Pueblos, Apache and

Navaho, made by McAllester and Brown in 1961. At that time the

collectors found that “among the Apaches almost nobody plays the flute

today.” ([McAllester 1960] The instrument made by the Apache is a whistle flute of river cane and has only three finger-holes. The range of this melody is limited to eight semitones (a perfect fifth) and its scale is tetratonic (d",f",g",a"). The melodic movement of each short phrase is in arch-shaped contours and gives the piece an overall undulating effect similar to that seen in the Flathead melodies. This feature conforms to Nettl's finding for vocal music of the Apache in which the melodic movement also tends to be in arc-shaped contours ([Nettl 1954], page 22). Intervals are small and step-wise movement predominates. There is some use of falling thirds; again, a similarity with Flathead melodies.

The rhythm of this melody is free and the tempo fairly slow

(M.M.

2.5 — Summary of Characteristics of Instrumental Love SongsIn summarizing the preceding discussion of twenty-six flageolet melodies, certain characteristics recur that can be considered features of an instrumental style while others show a similarity to the typical vocal style of a given area. The range of these melodies is, of course, dependent upon the instrument to a certain degree. Twelve to fifteen semitones is the average range; somewhat less than vocal music of the Western Great Lakes but about the same as for the Plains. The great difference is seen in the flute music of the Southwest where the Apache flute produces melodies of only half an ocatve's range while the vocal music of the area often covers one and a half octaves. Scales are most often pentatonic. This feature coincides with the general trend of vocal music in all areas discussed. Tetratonic and hexatonic scales occur less frequently and heptatonic scales are rare. In Western Great Lakes flageolet music, a melodic pattern of repeated descent from the highest note of the piece emerges as the most important type. Plains instrumental music modifies this feature somewhat by alternating straight descent with arch-form phrases. Arch-form and undulating contours are also frequent in flute music of the Plains, Plateau, and Southwest areas. Only vocal music of the Southwest has a majority of songs in arch-form. In contrast to these various melodic contours, the melodic line of vocal music from the Western Great Lakes and Plains is almost always of the ‘terrace-type’. An instrumental style is evident in the use of intervals and the many wide leaps of octaves, fourths and fifths that are idiomatic to flageolet melodies. A typical intervallic pattern is seen in Western Great Lakes and Plains music. Phrases begin with numerous large intervals and then towards phrase-endings become more restricted in movement and show a step-wise descent. Half of the Plains and all of the Plateau and Southwest melodies use small intervals of seconds and thirds, a feature which is typical of vocal music of the Plains and Plateau areas.

A very free rhythm characterizes flageolet music. Combined with

a wide distribution of durational values, this unmetered rhythm creates

a spacious and rhapsodic quality typical of instrumental love songs.

In the few melodies (Plains) where the distribution of note values

is not as wide, rhythmic figures recur to give unity to the music. A

slow to andante tempo (M.M.

Despite the improvisatory and rhapsodic impression created by a very free rhythm, large intervallic leaps, and a wide distribution of durational values, flageolet pieces always have a tightly constructed form. Music of the Western Great Lakes and Plains is most often binary in overall structure, with reverting forms most common internally. The iterative form is less frequent and progressive structures, least common. The reverting and iterative forms tend to compensate for the free rhythms by creating a structural unity through repetition. A distinctive feature of flageolet music is its use of the long-held tonic note as a structural divider. In Western Great Lakes and Plains music this tone almost always functions as an introduction and ending, and quite often clearly demarcates mid-sections and section endings. This, however, is not a feature of Plateau and Southwest flageolet music. Tones which are a fourth, fifth and octave above the base tone are also structurally important. Finally, there are a number of ornamental features which together create an idiomatic flute style. The most characteristic of these is the intense vibrato with which the tonic of the melody is played. Grace notes, an octave above the tonic and created by overblowing, are a typical feature and appear to be a cultivated effect. Grace notes within the melodic line, turns, mordents, and trills are commonly used, as are downward glissandi and rising releases at phrase endings. TranscriptionsSigns used in the TranscriptionsTranscribing Indian melodies in ordinary musical notation is somewhat like forcing a square peg into a round hole. it can be accomplished by dint of sufficient exertion, but the original form will have suffered. The vital part of these melodies can be expressed in our notation, but many a delicate nuance of wild and wayward beauty will have disappeared. (Henry F. Gilbert, “Note on the Indian Music”, in Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian, Volume 6 (Cambridge: University Press, 1911), p. 166.)

For song transcriptions in this section, please see pages 45–72 of the PDF file for the original thesis. Chapter 3 — Vocal Love SongsBefore proceeding to a discussion of their musical aspects, it is necessary to try to define love songs in terms of American Indian culture for it is insufficient and, as will be shown, incorrect to assume that an Indian love song carried sentiments similar to those of a love song in European culture.

There is conflicting evidence as to whether love songs associated

with courtship even existed in American Indian society before European

contact. On the one hand, Fletcher

([Fletcher 1911] You may go on the warpath. When you return I will marry you. Others, which are commonly termed ‘love songs,’ express loneliness for a close family member or sentiments of sadness and mourning for a child, wife, or husband who had died. Some of these are extremely touching in their simplicity. The following is the text of a song from the Tlingit in which an old man who is dying addresses his young wife: Shake hands. I want to hold your hand before I die. I'm going to be sorry about you when I die. ([Laguna 1972], page 1295). Closer to the notion of a love song in Western society are the “songs of affection” which might be sung by persons who had been married for many years. Among the Pawnee, for example, these were considered expressive of “honourable” sentiments and a clear distinction was made between this type of song and the “modern” love song which later developed in Indian society as a result of European influences. The Pawnee associated the singing of courting songs wich a lower class of people who lived near towns, worked for Europeans, and drank whisky. ([Densmore 1929a], page 96). As one Pawnee writer has rather strongly stated: “… charms, songs, etc., to lure women were furnished by sexual perverts who lived somewhat apart and were in social disrepute.” ([Murie 1914], page 640). It is quite probable that love songs were also viewed negatively by older people because they underscored the erosion of traditional parental authority in matters of marriage. Despite this rather negative status of love songs, Densmore acknowledges that they were very prevalent on reservations in the early decades of this century ([Densmore 1926], page 87) and that among the Chippewa they were a favourite form of musical expression ([Densmore 1931], page 16). A brief glance at the number of love songs that are included in her volumes on Chippewa music confirms this. Even in those songs which can be termed modern courting songs, texts did not often refer directly to another person expressing sentiments of affection. Rather, they tended to be songs of sadness, loneliness, or disappointment that were sung by oneself. Mention of weeping only occurs in love songs and is often associated with intoxication ([Densmore 1932a], page 210). The following song texts from the Chippewa are illustrative of the general tone of love songs: To a very distant land he is going, my lover, soon he will come again ([Densmore 1913], page 301). Other songs are more light-hearted and have a touch of humour. Of the following song, Densmore ([Densmore 1910], page 151) has written that “in the old times an Indian maid would lie face down on the prairie for hours at a time singing this song.” Why should I, even I be jealous because of that bad boy? From Menominee comes the following “taunting” song: You had better go home, your mother loves you so much. ([Densmore 1932a], page 210). To conclude this discussion of song texts, one final example of a love song, exhibiting a finely developed sense of poetic expression, is quoted: A loon I thought it was, Vocal love songs, like Ghost Dance and Peyote songs, have been considered a separate genre by a number of writers.1 As a special song type, love songs have characteristics which are unique to them and are not seen in other vocal music of a given area. How this song type may have evolved and a description of its features is the topic of this chapter. 1 Herzog includes vocal love songs as a distinct category in his “Special Song Types in North American Indian Music” ([Herzog 1935a], pages 23–33). Densmore repeatedly places love songs under a separate heading in Chippewa Music I and II and in Menominee Music, and discusses features that are unique to them. In Ethnomusicology of the Flathead Indian, Merriam takes up Herzog's theory of special song types in connection with his own study of Flathead Indian music ([Merriam-AP 1967], pages 316–321). Vocal love songs are generally found in the same geographical location as flageolet melodies and, as Herzog points out, this suggests a close connection between the instrument and the song type ([Herzog 1935a], page 27). In all probability vocal love songs derived from flageolet melodies. Quoting a native informant, Densmore ([Densmore 1932a], page 208) writes: “Long ago there was a kind of singing which had no words and was an imitation of the flute. This was intended as a love song and it was different from any other kind of singing.” It has been found that the Winnebago ([Herzog 1935a], page 27; [Densmore 1930], page 658), Dakota ([Herzog 1935a], page 28), and Pawnee ([Densmore 1930], page 658) also believed that love songs originated from flageolet melodies. If love songs are a result of a transfer from flageolet to voice, certain features of the instrumental melodies can be expected to recur in the vocal songs. Love songs will be discussed in this context and an attempt will be made to determine whether vocal love songs have greater similarity to their instrumental counterparts of to the typical vocal song style of a given musical area. For consistency and, in it hoped, clarity of organization, vocal music will be discussed according to the same geographical groupings as were employed in the previous chapter on flageolet melodies. 3.1 — Western Great Lakes/PlainsFor the study of Hestern Great Lakes love songs, a sample of thirty-one melodies is available. All but one of these have been collected and transcribed by Frances Densmore and are published in Chippewa Music I and II ([Densmore 1910] & [Densmore 1913]) and in Menominee Music ([Densmore 1932a]); Bulletins 45, 53, and 102 from the Bureau of American Ethnology.2 The Chippewa music was recorded by Densmore in 1908 and 1910 at White Earth, Red Lake, and Waba'cing in Minnesota and on the Lac du Flambeau Reservation in Wisconsin. In 1951 a long-playing recording, Songs of the Chippewa (L22), containing seven of these love songs was issued by the Library of Congress. These have been re-transcribed and are appended to this chapter as songs No. 20–26, pr. 112–121.3 Similarly, an album entitled Songs of the Menominee, Mandan and Hidatsa (L33, 1953) contains one Menominee love song and this has also been re-transcribed (No. 28, p. 123). Given a large body of material, no one piece will be discussed in detail, but since the purpose of this analysis is to distill the major characteristics of Western Great Lakes love songs, a large sampling should produce a fairly accurate picture.

2

For a complete list of the Densmore songs that have been analyzed,

see pages 106–107 of the

PDF version of this thesis.

The range of most Chippewa and Menominee love songs is 13 to 15 semi tones (18 examples); hmvever, another eight songs (or almost 26%) have very large ranges of one and a half to two octaves. Referring back to flageolet melodies, it was noted that the range of all the Western Great Lakes pieces lay between 12 and 14 semitones, while the average range for vocal music of this area was much larger. It would seem here that, in terms of range, vocal love songs have been influenced by both their instrumental counterparts and by the typical musical style of the area, but that the influence of flageolet melodies predominates. Scales are primarily pentatonic (12 examples) and hexatonic (7 examples). This corresponds to the previous finding for flageolet melodies; whereas typical vocal music of the area is usually based on pentatonic or tetratonic scales ([Nettl 1954], page 25). Some scales of seven tones and four tones occur (six and five examples, respectively) and one love song using only three tones was found.4 In general, songs with pentatonic scales have an average range of one octave while those based on hexatonic and heptatonic scales have the largest ranges. 4 The tritonic melody is anomalous to this group of love songs in many ways. Densmore ([Densmore 1913], page 300) relates that the singer had learnt this song as a young girl more than sixty years previous and it is quite possible that the repetitious text and bare triadic melody are a result of being imperfectly remembered. The melodic movement of vocal love songs in the Western Great Lakes area exhibits a fairly consistent pattern. In most songs, individual phrases have an undulating line but the tendency over the entire piece is one of gradual descent from highest to lowest tone. Songs 20, and 22–25 are good examples of this type of melodic pattern. A few love songs have an undulating line which starts or ends on or near the same tone (27, MM page 210 top) and three are simple arch-forms (21, 28, MM page 211 bottom). The type of descending line seen in flageolet melodies of this area is rare among their vocal equivalents. It appears that the melodic movement of vocal love songs corresponds neither to the typical vocal song of the Western Great Lakes, which is almost exclusively of the terrace type ([Nettl 1954], page 25), nor to the descending line of flageolet melodies, but ratehr is closer to the undulating contour typical of Eastern Woodlands style ([Nettl 1954], page 34). Unlike flageolet melodies which make frequent use of larger intervals of fourths, fifths, and octaves, the melodic lines of vocal love songs are smoother and contain smaller intervals. Most often love songs of this area have a step-wise movement but with numerous intervals of thirds and fourths interspersed (23, 25, 28). Occasionally intervals of thirds and fifths (27) or fourths and fifths (24) combine with a step-wise movement. Approximately 40% of all the vocal love songs employ small intervals of a major second and minor third (22) but even in these the interval of a fourth is still fairly prominent. Only two pieces (21, 27) exhibit the initial octave leap typical of flageolet melodies; however, the internal structure of thier melodic lines is smooth, with step-wise movement and a few thirds predominating. In general, the melodic intervals of Western Great Lakes love songs correspond more closely to the typical vocal style of the area; i.e., with thier use of smaller intervals of a second and third ([Nettl 1954], page 25), rather than to flageolet melodies. The free rhythms common to most flageolet melodies of the Western Great Lakes area are lacking in vocal love songs.5 The majority of songs reveal fairly regular rhythms and have underlying duple meters (22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28) or a triple meter (21). Only two pieces are rhythmically free (20, 24). In this sub-area, Nettl points out the frequent occurance of the isorhythmic principle in vocal music ([Nettl 1954], page 26). Although this feature was not observed in the flageolet melodies, seven of the vocal songs (20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28) contian isorhythmic phrases; i.e. phrases in which the rhythmic values of the notes remain the same even through pitches change. For example, the notes of the first, second, third, and final phrases of Chippewa songs 24 have the following rhythms (or very slight alterations thereof:

5 In this discussion of rhythm, Densmore's transcriptions have not been enumerated since, in re-transcribing the eight songs that were available on recordings, her rhythmic values were found to be unreliable and numerous changes were necessary. Similarly, the only available example of a Menominee love song is asymmetrically isorhythmic, being composed of two phrases which are then repeated:

The only melody of this group (27) which is sung with a drum accompaniment is strictly isorhythmic:

Vocal love songs of the Western Great Lakes do not have the same wide distribution of durational values found in their

instrumental

counterparts. Most of the songs are dominated by smaller note values,

** Editor's note: It is not clear what resource was intended by Mary Frances Riemer for the citation [Densmore 1951]. It may have been [Densmore 1910] or [Densmore 1913]. In terms of form, all songs exhibit a clearly defined structure. This finding, however, is in disagreement with Herzog who states that instrumental melodies and their vocal counterparts “often enough, consist of a similarly free and loose cumulation of phrases” ([Herzog 1935a], page 29). The majority of love songs from this area (60%) have an iterative structure (26, 27, 28). Progressive and through-composed forms account for another 28% (20, 21, 22, 23), but reverting forms are few (24, 25). This distribution of structural types does not correspond with Nettl's findings for typical vocal music of the area which is predominantly progressive ([Nettl 1954], page 26). Unlike the instrumental melodies, vocal love songs are not clearly divided into sections by long-held base tones and only one vocal song (21) has the repeated-note introduction which is typical of flageolet melodies. Even without repeated statements of the base note, the tonality of almost all vocal love songs is clear. The tonic is most often the lowest tone, towards which the whole melody gravitates, and it is usually the most prominent tone as well (22, 23, 24, 25, 26). Both flageolet melodies and typical vocal music of the area follow this pattern ([Nettl 1954], page 25). Occasionally a vocal melody will descend to a fourth below the tonic (27, 28) but without weakening the tonality. In vocal songs, fourths, fifths, and octaves above the base tone are not as consistently prominent as in flageolet melodies but are, nevertheless, important tones of the scale (22, 23, 24, 25, 28). Although a discussion of the preceding characteristics has revealed similarities between vocal love songs and their instrumental counterparts, two significant features, the manner of performance and vocal quality, clearly indicate their connection. These, however, are the most intangible features, impossible to notate adequately and very difficult to describe in words.6 The most readily apparent and striking characteristic of vocal technique is the nasal, drawling tone with which love songs are rendered (20–25, 28). According to Densmore, this nasal tone was used by the Chippewa and Menominee to imitate the sound quality of the flute ([Densmore 1932a], page 208). To further enhance this imitation, a singer would sometime wave his hand slowly before his mouth to interrupt the flow of breath and produce pulsations ([Herzog 1935a], page 28; [Fletcher 1893], page 11). The occasional single sharp call at the end of the piece (20, 23) is reminiscent of the typical high grace note ending of flageolet melodies. The unique manner of voicing of love songs almost demonstrates their similarity to flageolet melodies. For example, the rising flissando attack at phrase beginnings (21, 22), glissandi between wider intervals (20–25, 28), and rising (20, 23–24) and falling (22) releases are all features of instrumental love songs. Song no. 20 is perhaps the best example of the unique manner of performance of vocal love songs since it contains virtually all of the characteristics mentioned above. In addition, this song has one peculiarity of performance not heard in the other love songs. At the beginning of phrase B', the singer performs a sudden dimunendo and sings two ‘portamento’ notes on the vocable or syllable “mu-um.” Attempts at swelling or diminishing a tone are “sometimes noticable in love songs” ([Fletcher 1893], page 11) and, in this case, it sounds very like an imitation of a flute call. This manner of performance is remarkable since attempts at interpretative singing are almost unknown in American Indian music. 6 Densmore's transcriptions have not been included in this discussion as her notation gives very little indication of features beyond pitch and rhythmic not evalues. She does, however, repeatedly refer to the distinctive vocal style of love songs. 3.2 — Central PlainsVocal love songs from the Plains are are represented by ten melodies from the Sioux, Omaha, and Kiowa. 7 As a group, these songs are quite homogenous and have many features in common with flageolet melodies from the Western Great Lakes and Plains areas. 7 Three of these transcriptions from Fletcher, Alice C., The Omaha Tribe, page 320 (two Omaha pieces designated F4 and F5) and from Curtis, Edwards S., The North American Indian, volume 3, page 150 (one Sioux piece designated C2), for which no recordings are available. See transcriptions, pages 133–135. The range of all the Sioux and Kiowa love songs is a uniform thirteen semitones; i.e. a full octave. In this respect, they conform exactly to their instrumental counterparts; while the two Omaha melodies, with very large ranges of 23 and 27 semitones (just under and over two octaves), resemble some of the Chippewa love songs just discussed. The most common scale is tetratonic (30, 31, 32, 33, 34, C2), followed by hexatonic (35, F4). Only one melody is pentatonic (29) and one, heptatonic (F5). This finding is somewhat unexpected since pentatonic scales were seen in the majority of Plains flageolet melodies and they are also the most unusual scales for vocal music of the central and southern Plains ([Nettl 1954], pages 27 & 29). The melodic movement of vocal love songs of the Plains area exhibits two main patterns. The more prominent iss an undulating line (29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 34) which, in several instances (30, 32, 33, 34, 35) starts with a leap of a fourth, fifth, or octave to the song's highest tone before beginning an undulating descent. It will be recalled that this initial leap and gradual descent characteristic of flageolet Melodies from the Western Great Lakes and Plains area. The second type of melodic movement is ‘terracing’, a pattern very typical of Plains music but which has been noticeably absent from instrumental and vocal love songs. Both Omaha pieces and the Sioux melody from Curtis exhibit a terrace type of descent. The kinds of intervals used in vocal love songs of the Plains do not present a uniform picture. Four of the melodies (30, 31, 32, 33) contian wide leaps of fourths, fifths, and octaves and these usually occur at beginnings of sections, with step-wise movement predominant in the latter halves. This use of intervals is very similar to that seen in flageolet melodies of the Western Great Lakes and Plains areas. Compare:

Other melodies employ numerous fourths and fifths (34, 35, C2), while only three songs (F4, F5, 29) consistently use small intervals of seconds and thirds, a feature which coincides with the general trend of Plains vocal music ([Nettl 1954], page 29).

Like Plains flageolet melodies, vocal love songs from this area

exhibit fairly regular rhythmic patterns. Two songs (29 and 30) are the

vocal equivalents of flageolet meodies 8 and 9 which, it was noted,

had very regular meters and had probably been modified by European

musical influences.8 Excluding these, four songs remain that have some

regularity of rhythm: no 33 and C2 with an underlying duple meter and

no. 31 and 32 with an underlying triple meter. Rhythmic stability in

this group of Plains love songs is created in two ways; by a narrow

distribution of durational values and through the use of isorhythmic

material. For example, songs 31 and 33 are restricted to smaller note values

8 Those melodies having instrumental and vocal equivalents will be discussed in the following chapter. Only three songs are rhythmically free (34, 35, F4). In general, vocal love songs fron the Plains are rhythmically similar not only to Plains flageolet melodies but also to vocal love songs of the Western Great Lakes.

Most often vocal love songs are sung without accompaniment, but

in this group of Plains songs two Sioux melodies (32, 34) have a light

drum accompaniment. In song no. 32 the beat changes from

Recalling the structure of Plains flageolet melodies, it was found that those pieces were most often reverting (five examples) and only occasionally progressive or iterative (two examples each). The same distribution of form types has been found to occur in their vocal counterparts; i.e. five pieces have a reverting structure (F4, 29, 32, 33, C2), three are progressive (30, 31, 34) and two, iterative (35, F5). It is noticable that 90% of the Plains vocal love songs in this sample are clearly demarcated into major sections by long-held notes (29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, C2, F4). In all but two pieces (29, 31) this note is the tonic or base tone, creating both a structural and tonal clarity in these melodies. It will be remembered that this consistent use of long-held tonic notes was a striking feature of Western Great Lakes and Plains flageolet melodies, and to find it recurring in Plains vocal love songs strongly suggests a close connection between the instrumental and vocal forms. Because the tonic of these melodies is heard so often in prominent positions such as phrase and section endings, tonality in this music is usually very clear. As in Plains flageolet melodies, fifths and octaves above the tonic are important tones of the scale. The singing style and vocal quality employed in Plains love songs compare close1y to the style of performance of their instrumental counterparts but, because of this, differ markedly from the preceding group of Chippewa and Menominee love songs. It was noted that Plains flageolet melodies were played in a strong, bold manner. Long-held tones were performed with an intense vibrato and quick, sharp grace notes heard an octave above were common. In Plains vocal love songs this same kind of tension occurs in the voice and is indicated by pulsations on longer tones, grace notes, glissandi, rising attacks,and shaprly rising releases at phrase endings. Songs 31, 32, and 34 are excellent examples of this tense singing style. Pulsation and vocal tension are characteriatics of Plains singing style ([Nettl 1954], page 30) but are noticeably absent in the love songs of the Chippewa and Menominee. Only the Kiowa melody (35) resembles the Western Great Lakes style of singing in that it has a drawling, nasal quality and downward glissandi are common. No grace notes or rising releases; i.e., features indicative of vocal tension, are heard. In these Plains love songs, as in Western Great Lakes melodies, a remnant of the structure of flageolet melodies is seen in the brief sharp calls occurring at the end of several pieces (30, 31, 32, 34). To summarize briefly, Plains vocal love songs resemble their instrmental counterparts in a majority of their characteristics but consequently differ strongly from the typical vocal love song of the Western Great Lakes. 3.3 — PlateauIn the preceeding chapter on flageolet melodies it was noted that musical examples from the Plateau area were relatively few. While a larger sampling of eleven vocal love songs is available for discussion, here, the source of this music remains restricted as before to only two groups, the Flathead and the Nez Perce Indians.9 From the discussion of flageolet melodies, it was found that pieces from the Plateau bore little resemblance to those of the Western Great Lakes or Plains, having features that were unique to themselves. It will be shown that many of these characteristics are repeated in their vocal counterparts but that, at the same time, both the melodic line and the singing style are reminiscent of vocal songs from the Western Great Lakes area. 9 Two Flathead vocal love songs (36, 37) have been transcribed from Alan P. Merriam's recording, Songs and Dances of the Flathead Indians; eight additional love songs appear on pages 188–191 in his Ethnomusicology of the Flathead Indians; and C3 is a Nez Perce melody taken from Curtis, The North American Indian, volume 8, pages 184–185. See transcriptions for 36, 37, and C3 on pages 136–140 of the PDF version of this thesis. The tonal ranges of the Plateau love songs fall into two groupings: those with a narrow range of 7–9 semitones (or approximately one-half octave) and those of 12–17 semitones (an octave or more). The scales of these melodies vary widely from tetratonic to heptatonic; howe3ver, four of the eleven songs are pentatonic and in this respect resemble Flathead flageolet melodies. Three of these scales have a tendency towards chromaticism (e.g., 36) and the consistent use of flissandi between notes of narrow interval enhances this feature. All of the vocal love songs in this group have generally undulating melodic lines. Seven of these incorporate a downward trend (these also tend to be songs with ranges of an octave or more) while the four remaining pieces begin and end at about the same level. It will be recalled that the melodic movement of flageolet melodies from the Plateau and of the vocal love songs of the Chippewa and Menominee is very similar. No examples of the more pronounced descending pattern typical of Plains instrumental and vocal love songs occur. The intervals use in these songs are generally small; fourths are the largets intervals employed, (e.g., 36). Again, the vocal love songs and their instrumental counterparts are alike. Like the majority of love songs both instrumental and vocal, the rhythm of these Flathead melodies is very free. The distribution of durational values is wide and, in the absence of a regular drum-beat, in part creates the unmetered rhythms. Song 36, for example, repeatedly employs thirty-seconds and whole tones in the same short phrase which is freely sung as a melisma on the vocable ‘he.’

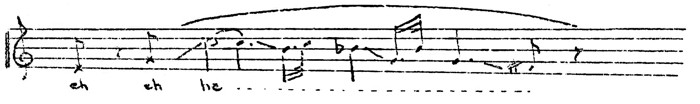

A slow tempo is typical of all Flathead love songs and is characteristic of instrumental and vocal melodies from all the areas examined. In terms of formal structure, six pieces are progressive and five are reverting (36, 37). More than one half of the Flathead melodies show variants of incomplete repetition. The Nez Perce love song (C3) is an example, unusual in love songs, of a very long piece which is essentially through-composed. There are three sections within the song that can be identified as variations of each other but, unlike most other pieces, no clearly defined sections are observed. Flathead vocal love songs, like their instrumental versions, do not have long-held tones that provide distinct introductions, mid-section, or endings. In this respect, they are similar to vocal love songs of the Chippewa but differ from both the instrumental and vocal melodies of the Plains. Tonality is fairly clear in this group fo Flathead love songs even in those that are heavily chromatic; e.g., 36. In song 37, d' is a rather weak tonic since it is not the most prominent tone and occurs only infrequently at phrase endings. As pointed out previously, it is the Flathead singing style that connects it to vocal love songs of the Western Great Lakes. The drawling vocal quality, glissandi, and falling releases so distinctive of those songs are heard again in the Plateau area. 3.4 — SouthwestVocal love songs from the Apache, like their instrumental versions, are rare in comparison to musical examples from other areas. Whether this is a modern development or was always the case is unknown. The one song available is in the typical vocal style of the area ([Nettl 1954], pages 22–23) but bears little resemblance to the Apache flageolet melody discussed earlier. Many features, however, are similar to vocal melodies of the Plains.

The range of the Apache love song is one and a half octaves and

the scale is tritonic. Melodic movement is in the shape of wide,

undulating arcs which cover the full range of the scng. The initial

leaps up to the highest point of the melody as well as the consistent

use of larger intervals of forths, fifths, and octaves are reminiscent

of both the instrumental and vocal love song of the Plains. Like Plains

vocal melodies, this Apache song has a fairly regular rhythm, created

by the repetition of one rhythmic figure,