|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Frequently Asked Questions for the Native American FluteThis page provides some answers to questions about the Native American flute. It is mostly designed for players of the instrument. Some questions about flute crafting are also addressed, but please see the FAQ for Crafting for more in-depth information. The content provided on this page is distilled from sources I have found while developing this Flutopedia web site, and is based on my best understanding at the time I wrote it. See the cited sources for more information. Questions that begin with “…” are follow-on questions that relate to the question before them. For example: … this is a follow-on question that relates to the prior question and answerOne more thing: please realize that some of these questions lead to rabbit hole topics. Questions that appear to be a straightforward lead to answers that get progressively more murky, with caveats, special cases, and historical issues popping up that take you farther and farther from what you hoped would be a straightforward answer. AcknowledgementsMany folks have contributed to this page, both in proposing questions and providing content. These folks include: Bette Acker, Brent Adams, Bob Carlson, Terry Green, Lenny Henderson, Barry Higgins, John Hnath, Cornell Kinderknecht, Helen Mayernik, David Mellor, Terry Noble, Mike Prairie, Glenn Prun, Redbeard, Justine Shrider, Dave Sproul, and Erik Weaver. Table of ContentsHere are links to the major sections of this FAQ:

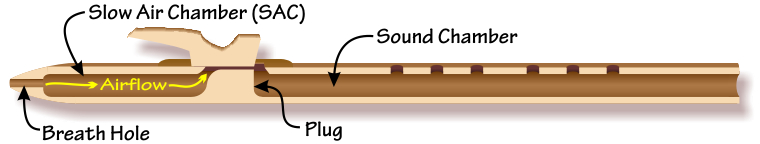

BasicsWhat is a Native American flute?A Native American flute is a flute that is held in front of the player, has open finger holes, and has two chambers: one for collecting the breath of the player and one which is designed to resonate and create sound. The two chambers, called the “slow air chamber” and the “sound chamber”, are separated by a “plug”. Air is directed from the slow air chamber to the sound chamber by a channel called a “flue”. The flue is formed by a combination of the body of the plug, the body of the flute, and an external “block”. The phrase “open finger holes” means that the finger holes on the instrument are closed by your fingers, rather than keys or mechanical mechanisms.

This description is based on the definition provided by R. Carlos Nakai on June 21, 2002 as “A front-held, open-holed whistle, with an external block and an internal wall that separates a mouth chamber from a resonating chamber.” There are a few elements shown in the diagram above that are not central to the design of the instrument: the strap is optional and the nest and breath hole have many configurations in various designs of the instrument. Also note the things that are not mentioned: there is no specified number of finger holes, spacing between the holes, or shape of the various components. How do I get started playing?It is difficult to surpass the eloquent description provided by Michael Graham Allen to accompany flutes he crafted in the late 1980s. Here is are photos I took of those four pages, from an original in the collection of Jon Norris. However, note that Michael is describing a flute with a brass spacer — many flutes do not use a spacer, and have the block sitting directly on the roost. Click on each page to see a larger description:

I have additional holes near the foot end of my flute — what are they?

One or more holes nearest the foot end of the flute are called direction holes. They are not intended to be covered during normal play. What does a Native American flute look like inside?

If we cut a flute in half (……shudder……) it might look something like the diagram above. See the Flutopedia page Anatomy of the Native American Flute for a description of each of the components. How is the sound created?Take a piece of paper and hold one edge tautly between your fingers. Bring it up to your lips — maybe a half inch away — and blow a thin stream of air against the taught edge. Can you make a whistling sound? It might take some experimenting to get this feeble, high-pitched airy whistle, but most people can get this sound. It is called an edge tone, and it is the beginning of the sound of every note on the flute. A similar edge tone occurs when an air stream travels out of the flue and hits the splitting edge, shown here in this cutaway view of the design of the inside of the flute in the area of the nest and block:

However, this edge tone is not usually sustained, because the physics of the sound chamber of the flute come into play. The air stream that alternates above and below the splitting edge sets up a resonating column of air in the sound chamber. As long as the air steam continues, the resonance in the sound chamber continues in a (predominantly) steady vibration of the air column. That air column causes an oscillating wave of air pressure, called a compression wave, to fan out from the flute. The graphic at the right demonstrates a single wave of air pressure change moving from left to right. That wave of alternating higher-pressure and lower-pressure air that reaches our ears, moving small hairs inside our ears. As the small hairs move, tiny electrical impulses are generated in nerves leading to our brains, and we interpret (or some would say “we have learned to interpret”) those impulses as sound. See the Flutopedia page Anatomy of the Native American Flute Flute for a description of each of the components. Why are some flutes called “Native American style flutes”?A United States law, the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, was established to protect products crafted by members of federally or State-recognized Indian Tribes. Only those products can be represented as Indian-made. So, from a truth-in-advertising perspective, only flutes made by members of federally or State-recognized Indian Tribes can be represented as a “Native American flute” or “American Indian Flute”. In those situations of advertising or representation of specific flutes offered for sale, makers will often use terms such as “Native American Style Flute” or “North American Flute”. However, while this responsibility applies as a matter of truth-in-advertising when talking about a specific flute by a specific maker, it does not extend to our discussion of the instrument as a whole. On this web site, I use the term “Native American flute” freely when discussing the design, playing, and body of music for the instrument. How is the Native American flute different from other woodwind instruments?Most wind instruments you have likely encountered — clarinets, oboes, English horns, bassoons, saxophones, recorders, and Western concert flutes — are different in both design and philosphy from Native American flutes. In addition to the design differences, there is a culture of flute makers who create instruments of their own design and orientation, in contrast with makers of recorders who work towards very similar design goals. The community of Native American flute makers produces a huge variation in Native American flute designs, which continues the tradition of innovation and creativity in the craft. All these development have come with some tradeoffs versus an instrument such as the recorder:

How old is the Native American flute design?The earliest known Native American flute is the Beltrami Native American flute, shown below. It was collected by the Italian explorer Giacomo Costantino Beltrami on a journey through present-day Minnesota in 1823.

There are several artifacts, in particular the Breckenridge flute, that might qualify as Native American flutes, but there is not yet consensus nor sufficient research on those artifacts. … but I thought that flutes are far more ancient than 1823?They are. Flutes, in general, date back at least 33,000 years. Flutes in North America date back to at least to about 5580 BCE. However, the specific instrument design of the Native American flute is not known to exist before 1823. Were flutes made by indigenous North Americans before 1823?Yes. The Flutopedia pages A Brief History of the Native American Flute and The Development of Flutes in North America trace the development of flutes in varying amounts of detail. In particular, there were some fascinating flutes crafted in 620–670 CE in present-day Arizona. However, all known North American flutes before 1823, although crafted by Native Americans, are not of the design (described above) that we now call the “Native American flute”. What is a contemporary Native American flute?The term “contemporary Native American flute” is currently in limited use in the community, but is useful in describing a class of flutes that all play basic songs using the similar finger patterns. It denotes a Native American flute tuned to what has become the predominant tuning arrangement since about 1980. If the flute is described as a “minor key flute”, “pentatonic minor flute”, or is “in the key of [something] minor”, then it is likely to be a contemporary Native American flute. What do historical or traditional Native American flutes sound like?The New Age movement beginning in the early 1970s had a substantial impact on the style of music that is typically played on the Native American flute — to the point where the Native American flute became known, in some circles, as a “New Age instrument”. However, the style of music pre-dating the New Age music was quite different. An excellent example is this recording of Belo Cozad's Kiowa Story of the Flute collected by Willard Rhodes in Anadarko, Oklahoma, in the summer of 1941. Liner notes by Willard Rhodes from the Rounder Record publication follow. Kiowa Story of the Flute (excerpt) Belo Cozad. Track 30 of Library of Congress: A Treasury of Library of Congress Field Recordings (recorded 1941). This story by the renowned Kiowa flute maker Belo Cozad (1874-1950) provides another look at the folk process from a non-European American perspective. In his story Cozad establishes a kinship that he now extends to his audience, Indians and others alike. His evident willingness to share a precious musical heritage with society in general – “And keep it, keep it as long as you live” — is a healthy contrast to the balkanization of so much current thought and effort in cultural matters. Many of the Archive’s field notes reflect the comments of performers on how they first took up their instrument or otherwise relate the special events that caused them to become musicians. In this recording Belo Cozad describes an ancestor who went up on a mountain and, after four days, received this music from a spirit. Subsequently, Cozad himself received that music as a gift. The piece he plays on his handmade cedar flute is rooted in that particular experience. Cozad’s account is not as exotic as it might at first seem. W.E. Claunch’s daughter said of her father’s abilities: “It was just a natural talent God had given Daddy.” Katherine Shipp also spoke of her mother, Mary, whose aptitude for composition came as a “revealin’ to her.” Time and again musicians have attributed their music as coming from spiritual powers or from someone they admire. Either way, the transfer of music in the human community proceeds by gift. And this Belo Cozad articulates with heartwarming grace. For information on ethnographic recordings of flutes, see Ethnographic and Reference Flute Recordings. What is the range of a Native American flute?The span from the lowest note of an instrument to the highest note the instrument can play is called the range. Since the design of the instrument varies quite a bit across the community of flute makers, different individual instruments have different ranges. Most Native American flutes have a range of at least one octave, and many can extend into the second register to get one or a few more notes. Some makers intentionally craft extended-range flutes — designing their instruments to get a additional notes in the second register and/or optimizing the tuning of those upper notes. You may see statements that a particular flute has a range of 1.3 or 1.4 octaves, indicating that some number of notes in the second register are attainable. Selecting a FluteWhat does it mean when a flute is in “F# Minor” or in “the key of A”?These types of indications for a particular flute tell the “key” of the flute. The key of a Native American flute is the lowest pitch that is normally played on that flute, together with a general indication of the mode of the primary scale of the instrument. The pitches are: C, C# (same as Db), D, D# (same as Eb), E, F, F# (same as Gb), G, G# (same as Ab), A, A# (same as Bb), and B. The mode of the primary scale on a Native American flute is typically “minor”, but flutes can be made in “major” (also called “diatonic”), “Byzantine”, “blues”, and many other tunings. See Keys of Native American Flutes for sound samples of various keys. What is the difference between “minor” and “major”?There is a tremendous amount that can be (and has been) written about this issue. However, nothing demonstrates the difference between minor and major like listening. Here are some recordings: The sound of a minor chord — three notes plus an octave note — on an F# Native American flute: Minor Chord Clint Goss. After you start this audio player, it continues to play in a loop. Click the stop button on the audio player to silence this audio stream. F# minor flute by Steve Petermann. You'll note that, in all of the recordings in this section, I'm playing the notes very quickly (as fast as I reasonably can, actually) in order to give you the feeling of a complete chord. The sound of a major chord — three notes plus an octave note — on an F# Native American flute: Major Chord Clint Goss. After you start this audio player, it continues to play in a loop. Click the stop button on the audio player to silence this audio stream. F# minor flute by Steve Petermann. The sound of a six-note (hexatonic) minor scale on an F# Native American flute: Minor Hexatonic Scale Clint Goss. After you start this audio player, it continues to play in a loop. Click the stop button on the audio player to silence this audio stream. F# minor flute by Steve Petermann. The sound of a six-note (hexatonic) major scale on an F# Native American flute: Major Hexatonic Scale Clint Goss. After you start this audio player, it continues to play in a loop. Click the stop button on the audio player to silence this audio stream. F# minor flute by Steve Petermann. So what do you think is the feeling of minor versus major? There's plenty of opportunity to read what others think of the difference, but, as a musician, the important thing is what you think of the difference. If you'd like to recreate the difference above on your own flute (much more slowly, at first), here are the fingerings I used: Minor chord:

For more on this, see the section below on Music Theory Basics. What key should I get for my first flute?Most people are drawn to the Native American flute by the sound of the instrument, and it is natural to look for a flute in the same key as the sounds you enjoy most. However, there are some practical considerations. Primarily:

It all comes down to the geometry of your hands and arms. I have found that people with relatively larger hands and/or longer fingers are often comfortable with mid-range Native American flutes in the keys of F# minor or G minor. People with relatively shorter fingers and/or smaller hands tend to be comfortable with a mid-range A minor flute. These would probably be good starting points if you have no other reference to sizing for your particular body geometry. Once you get comfortable with holding the flute with relaxed hands and covering the finger holes with the pads of your fingers, you can branch out and try flutes in higher and lower keys. What is the best key to get if I want to play with a guitar?Experienced guitar players can work with any key of flute. Guitar players with less experience will be most comfortable playing with flute in the keys of: A minor, D minor, and E minor. Beginning guitar players should check out these two pages that describe simple one-finger chords that work with many Native American flutes: How much do I need to pay to get a reasonably good flute?I believe that Native America flute players are blessed by a close association with a large community of flute makers. A recent check of just one Internet newsgroup where flute makers share information shows 3,851 registered participants. Most flute makers craft each flute individually and most flutes are crafted entirely by a single person. This allows players to have a direct link to the flute maker, knowing them personally in many cases. It also means that the path for many flutes from maker to player is direct — there are no intermediaries, allowing a substantial portion of the cost of a flute to directly support the flute makers. Within that picture, there is a huge range of “price-points” for flutes. The majority of flutes retail in the range of $50–$600 (USD). How many flutes do I need?This question spawns a lot of jokes about “Flute Acquisition Syndrome”. Many flute players will tell you that no matter how many flutes they have, they need “another one”. However, Native American flute players do tend to own a lot more instruments than players of Western orchestral instruments. Here are a few reasons:

Should I get a commissioned flute or an off-the-shelf flute?Many flute makers will build custom flutes to your specifications and design. This can be a great choice for flute players that have very specific requirements for key, tuning, or scale, materials, adornments, etcetera. Also, if you have specific physical characteristics or limitations, this may be the best route. However, I generally recommend that, for a first Native American flute, players start with a straightforward flute of a basic, “off-the-shelf” design in the mid-range. What are the differences between six-hole and five-hole flutes?The short answer is: surprisingly little. Playing the primary scale on a typical six-hole Native American flute involves keeping the third hole from the top covered at all times:

… so, you are really only using five holes for that primary six-note scale. Those five holes are exactly the holes on a typical five-hole Native American flute! Here is the primary scale on a typical five-hole Native American flute:

However, once you go beyond the primary scale (the Pentatonic Minor scale, on most Native American flutes), there are some subtle differences between six-hole and five-hole Native American flutes. The finger holes on my flute vary in size and/or are not spaced evenly — is that normal?Yes. The finger hole spacing and the size of each finger hole affect the pitch of the notes produced by the flute and how comfortable the flute is to play. If the finger holes are too far apart, the flute can be uncomfortable of impossible for some players to reach and reliably cover the finger holes. I have a piece of leather tied in the middle of my flute — what is that for?If you see only five finger holes on your flute, it is likely that the leather covers up a sixth finger hole! Some makers add the leather strap to make their six-hole flutes into a five-hole flute. You are free to remove the leather and explore the options offered by the additional finger hole. How does a plastic flute compare with one made of wood?Some flutes today are made of various plastics: in particular, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). Here are some things to consider:

… and are there safety concerns with using plastics for flutes?Since you place a flute on your lips when you play, the safety of the materials and the finish of the flute should be considered. Not only should the characteristics of the material itself be considered, but the process used by the specific manufacturer of the material used in the flute. Is the material produced from recycled or re-ground products? What contaminants might be present? Considering the way flutes are used, I believe that plastic materials should meet one of the standards for:

While such “food-grade” or “food-compliant” grades of both PVC and ABS plastics are available (see, in particular, the manufacturers Curbell Plastics and Sabic, respectively), many of the commonly available sources of plastics are not suitable. Consider that the commonly available Schedule 40 PVC is designed for wastewater systems. So you can ask the flute maker about the source of their materials and what statements or certifications they have from the manufacturer about the specific grade of material used. However, realize that a statement by the manufacturer is different from a certification by an organization such as the FDA. Here is an excerpt from an email from Gary Bakker, of PolyChlor (personal communication, July 16, 2013) that highlights the situation: As in many cases with specific tests or ratings in the plastics industry many suppliers will use all the correct ingredients to meet a certain test but will not do the tests as they are extremely expensive and will have to be re-done if any changes are made in their process. This happens a great deal in the industry and various ingredients either change or come from different suppliers etc. So, if someone is running something specifically for the food industry, they will have to have FDA and keep their rating in place but many others in the industry who are on the periphery will suggest their material is FDA compliant but not approved. So, if you receive a statement by the manufacturer regarding the safety of the material as it relates to food safety standards, you will have to judge if it is sufficient for your needs. How do flutes made of plant stalks such as yucca, sunflower, sotol, and agave compare with flutes made of wood?Stalk flutes flutes generally take less time to craft that flutes made of wood. Many makers of stalk flutes craft their instruments using only hand tools. There is often lively discussion as to whether stalk flutes “sound different” from flutes made of wood, but there is no general consensus on this issue. Since each flute has its own unique sound, and quality instruments can be made by experienced flute makers from a wide variety of materals, the sound of an instument has more to do with crafting technique than the materials used. (Thanks to Ki-e-ta of Cherry Cows Flutes for addressing this question). Does the type of wood used in the construction of a flute affect the sound or voice of the flute?This is a topic of much debate, typically involving polarized views expressed with great fervor. In short, a rabbit hole topic. In musical instruments such as violins and guitars, where the body of the instrument acts as a resonator, nobody argues that the material can dramatically affects the sound. But for wind instruments where the body of the instrument does not (significantly) resonate, the debate is not so clear. One camp supports a position that the material has no more than a miniscule effect on the sound. They measure the sound generated by the body of the woodwind instrument versus the resonating air column ([Backus 1964]) and perform experiments where subjects play and listen to identically shaped wind instruments made of different materials ([Coltman 1971]). Arthur Benade sums up this side of the argument ([Benade 1990]): The question of whether or not the playing properties of wind instruments are influenced by the material from which it is made has been the subject of curiously bitter controversy for at least 150 years. … Since 1958 I have made several studies of the possible difference in damping that can be made by using copper, silver, brass, nickel silver, or various kinds of wood as the air-column wall material. If the walls are thick enough not to vibrate and if they are smooth and nonporous, experiment and theory agree that switching materials will make changes in the damping that are generally less than the two-percent change that most musicians are able to detect. The other camp opines that the vast differences sound between various Native American flutes is due in significant part to the materials used. Tom Stewart of Stellar Flutes provides a counterpoint on his web site: Each flute has its own voice and there are similarities in the woods of the same species or density. It is not an easy task to describe in words the nature of these various differences. Once a friend, also a flute maker, used the words “sweet and mellow” to describe the voice of flutes made of hardwoods like Cherry or Walnut. He called flutes made of soft wood like Western Red Cedar “crisp and clear”. I have always told my customers exactly the opposite. Yes, the wood used in the flute affects the voice, but you can see the dilemma created by trying to describe these subtle differences The reality is probably somewhere in the middle. Some issues that are typically not considered:

Here are some links to interesting publications on the subject:

Why do some flutes have a groove in the flute body and others have the groove in the base of the block?

The “groove” is a channel that directs the airstream toward the splitting edge. It is called the flue in the diagram above. This channel can be cut into the body of the instrument or into the bottom of the block — or even a combination of these two choices. The choice is a matter of taste for the flute maker. The block on my flute has extensions on the side — what are they for?Those extensions are called wings. They affect the timbre of the flute, the pitches of the notes produced, and can help keep wind from disturbing the vibrations that create the sound of the flute.

Are blocks on different flute interchangable?Not generally. The differences between block designs can be substantial. See, for example, the question above on Why do some flutes have a groove in the flute body …. Swapping a block which has the flue cut into the bottom with a flat-bottomed block will likely not get good results. More subtle differences deal with the shape of the face of the block — the side that faces the splitting edge. The precise shape of this face has a subtantial effect on the tuning of the flute. The photo at the right shows two blocks. Although you cannot see it in the picture, both blocks have a flat bottom (the flue is cut into the body of each flute). Also, neither of the blocks has wings. In this case, although the flute makers might object, you might be able to swap the blocks. Why would you want to? Here are some scenarios:

PlayingWhat is the proper placement of the flute in my mouth?Everyone has their own approach to this, and it does depend somewhat on the shape of the mouthpiece area of the flute. However, it's best to not think of placing the flute “in your mouth”. Try resting a small part of the mouthpiece on your lower lip and then using your upper lip to create a gentle, but airtight, seal. Does it matter which hand you place “on top” (closest to your mouth)?Regardless of which hand is dominant, most people play the Native American flute with their left hand nearest their mouth. However, you can certainly play Native American flutes either way. The only issue that I know of is that some makers, especially for lower keyed (larger) flutes, will offset the finger holes from the centerline to make them easier to reach. They typically assume “left hand nearest the mouth”, so those flutes would be very difficult to play if you played with your right hand nearest your mouth. If you have already begun to play the flute with the non-standard orientation (right hand nearest your mouth), then only you can decide if it is worthwhile to backtrack a bit and switch to the standard orientation. Another consideration is based on whether one of your hands has a wider comfortable spread when you stretch out your fingers. Hold both hands up with palms facing each other and spread your fingers wide apart. Compare the distances on each hand from your index to your ring fingers. If they are different, then yout might consider placing the hand wiith the larger spread on the finger holes at the bottom (foot end) of the flute. When you play lower-keyed flutes, these finger holes tend to be spread out more than the upper set of finger holes.

My flute does not make a sound — what do I do?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key of Flute | ||

|---|---|---|

| B | ||

| Bb / A# | ||

| A | ||

| Ab / G# | ||

| G | ||

| Gb / F# | ||

| F | ||

| E | ||

| Eb / D# | ||

| D | ||

| Db / C# | ||

| C |

Can you find one or a few rows that sound good with ![]() ? If so, switch to the fingering with the three bottom holes open:

? If so, switch to the fingering with the three bottom holes open:

![]() or

or

![]() .

Try matching that fingering with sound samples from the second column. If you find a row that works for both

.

Try matching that fingering with sound samples from the second column. If you find a row that works for both

![]() in the first column and

in the first column and

![]() in the second column, it is very likely that your flute is in the last column.

in the second column, it is very likely that your flute is in the last column.

The sound samples above are part of a set of Reference Drones that you can use to explore tuning and also experiment with playing your flute over a drone. Visit the Reference Drones page to explore this in more depth.

In addition to these methods, you can use an electronic tuner. Visit Flutopedia's Electronic Tuners and the Native American Flute page.

How can I tell if my flute is correctly “in tune”?

This is a bit of a rabbit hole topic.

As a beginning flute player, you probably want to know if:

- The flute will sound good when played solo.

- The flute will sound good when played with another instrument, such as a guitar or piano.

These are two rather different (but related) questions. If you are a beginning player, my short anwer to these is:

- Does the flute sound good, to your ear, when you play it solo? You might even go as far as to record your playing and listen back to it.

- Does the music you make when playing with those other instruments sound good to your ear?

If the instrument does not sound good in either of these situations, the answer is likely to deal, at least in part, with how much breath pressure you use when you play. Breath pressure plays a huge role in the pitches produced by a Native American flute. Other factors are room temperature, whether the instrument has been warmed-up, and the position of the block.

Also, realize that there is no single “correct” tuning. There are many different tuning standards from many different music cultures. They have evolved over time, and, in a marvelous example of co-evolution, the listening preferences of those cultures have evolved to prefer (and have strong positive emotional reactions to) the tuning system of their own culture. Listeners from one culture often hear the music from another culture with a different tuning system as “out of tune”.

If you are purchasing a flute you have not yet played, it is difficult to predict whether the flute will work for you. Some makers add the moniker “concert-tuned” to their descripitions, but this might not be a reliable indicator. The best insurance is to ask the maker if you can return the instrument if you are not happy with it.

If you continue to have trouble with tuning, it is probably best to seek the help of an experienced flute player.

And, i f you want to dive deeper down this rabbit hole topic, see my Right in Tune article.

What things can I do as a player to alter the overall tuning of a flute?

Here are some factors that the player can use to control the overall tuning of a Native American flute. “Sharper” means higher overall pitches/frequencies and “flatter” means lower overall pitches/frequencies:

- As you add more breath pressure, the flute gets sharper. Lower breath pressures tend to make the flute flatter.

- As you move the block toward the foot end of the flute, the flute typically gets flatter. Moving the block toward the head end typically makes the flute sharper. However, realize that the effect is more pronounced on the higher notes of the instrument (for example:

and

and  )

compared with the lower notes (for example:

)

compared with the lower notes (for example:  and

and  ).

Moving the block also affects the timbre of the instrument and the tendency to overblow.

).

Moving the block also affects the timbre of the instrument and the tendency to overblow. - As the temperature inside the sound chamber rises, the flute tends to get sharper. Lower temperatures correspond to flatter pitches. Several factors affect the temperature inside the sound chamber, including the ambient (room) temperature and the tendency for the air in the sound chamber to get warmer as you play for a while. See CrossTune for more information on this effect (including a graph of how the parts of the flute warm up).

- Finally, in rare cases it might be possible to swap the blocks on two flutes and change the tuning. This is discussed in the question Are blocks on different flute interchangable?

Here are some things that affect pitch minimally or not at all. They are listed here because of prior discussions and confusion about the effect of these factors:

- Humidity. By experimenting with the CrossTune tool, you can see that humidity has a very small effect. At 72°F, there is only a difference of 7 cents between the minimum of 0% relative humidity and the maximum of 100% relative humidity.

- Altitude. As altitude increases, there is a decrease in both air pressure and air density. In addition, there is a tendency for air temperature to decrease. While pressure, density, and temperature each affect the speed of sound, it turns out that the effects of decreased air pressure and decreased air density cancel each other out (see [Sengpiel 2009]

for a one-page writeup on this topic, and [Everest 2001] for a complete treatment). So, we are left with only the temperature variations that directly affect pitch.

for a one-page writeup on this topic, and [Everest 2001] for a complete treatment). So, we are left with only the temperature variations that directly affect pitch.

While temperature tends to decrease with altitude, some authors (in particular, Lew Paxton Price's series of books beginning with [Price 1990]) have used altitude directly in their formulas for pitch. However, I believe that this tends to mislead the flute community. It is better to measure the temperature directly and consider that altitude does not have a direct affect on changes in pitch.

What is the best position for the block?

A good first approximation is to position the block so, as you look down at the sound hole, the face of the block is on the edge of the sound hole – right on the edge, but not covering up any of the sound hole. From there, finding the best position for the block is a deep listening exercise.

|

|

|

Block positioned far back, near the likely sweet spot, and far forward over the sound hole

|

||

The pictures above show three positions for the block. The relation of the front edge of the block to the back edge of the sound hole is the important element. These are somewhat extreme positions — probably the limits of how far back and forward you would place the block:

- In the leftmost picture, the front edge of the block is far back from the sound hole. You can see the bottom of the flue. This is likely to produce a relatively breathy sound.

- In the center picture, the front edge of the block is close to and slightly behind the back of the sound. This is likely to be close to the sweet spot for most Native American flutes.

- In the rightmost picture, the block is positioned very far forward. The flute is likely to sound “thin” and will also tend to overblow more easily.

For more information, see position of the block.

|

What are “cents”?

A cent is a very small unit that is used to measure differences in pitch or frequency. The span of pitch between any two notes (for example, between C and C#) is divided into 100 cents.

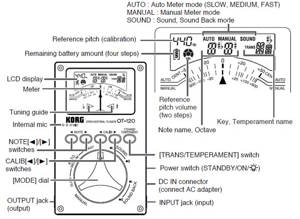

Some flute makers use electronic tuners such as the one show at the right. These tuners measure a steady pitch and display the precise tuning of that pitch. The note is displayed at the top (in this case “A4”), and the precise pitch is shown by a needle. If you look very carefully at the display (or click on the picture to see a larger image), you will see a scale underneath the needle that reads “CENT –50 … –20 … 0 … +20 … +50 CENT”. The needle will read the number of cents below (flatter than) A4 or above (sharper than) A4.

A difference in pitch of a single cent is too small for the human ear to hear — two pitches need to be at least three cents apart for most people to tell the difference. However, pitches that are 25 cents apart are very noticable to most people.

What is “A440”? (or “A=440” or “A=432” or “440 Hz”)

Most discussions about pitches and harmony deal with notes as they relate to each other. When we say that one note is an octave above another note, we are saying that the frequency of the higher note is double that of the lower note.

In contrast to relative tunings, a notation like “A=440” (or “A440”, or “A4=440 Hz”) tells us the actual frequency of a single note, called A4 (the A above middle C on a piano). The “440” indicates 440 Hertz, or cycles or air compression/decompression per second. A notation such as A4=440 is called a pitch standard.

When you fix one note to a specific frequency, you can calculate (after some math) the frequencies of all the other notes. For example, setting A4 to 440 Hertz means that the note an octave higher, A5, will resonate at 880 Hertz. If you are using an electronic tuner such as the Korg OT-120 shown above and diagramed below, you can set your pitch standard for A4 and let the tuner handle all the math. Both of the images show the tuner set to a pitch standard of 440 Hertz:

|

A group of musicians, such as an orchestra, will typically agree on a pitch standard. However, that standard can change from one setting to another, and has historically changed quite a bit over time. While “A440” is currently a widely-used standard, many other standards have been used historically.

Currently, there has is a lot of discussion of the various qualities of the pitch standards, especially the pitch standard A4=432 Hz. Rather than delving into that discussion (which you can easily access with a Web search), I think it's helpful to listen to some recordings! The next four audio players let you compare identical recordings — my playing of the E pentatonic minor scale — at four different pitch standards. Here is A4=440 Hertz:

Pentatonic Minor at A=440 Hertz

Clint Goss.

After you start this audio player, it continues to play in a loop. Click the stop button on the audio player to silence this audio stream.

E minor flute of Spalted Maple by Barry Higgins.

![]()

This next recording uses a pitch standard of A4=432 Hertz. It is 1.81819% or about 32 cents lower (flatter) than A4=440:

Pentatonic Minor at A=432 Hertz

Clint Goss.

After you start this audio player, it continues to play in a loop. Click the stop button on the audio player to silence this audio stream.

E minor flute of Spalted Maple by Barry Higgins.

![]()

Can you hear the tuning difference between the two recordings above? You can even play two recordings simultaneously and hear the dissonance created by the tuning differences.

This next recording uses a pitch standard of A4=415.305 Hertz. It is 5.6125% or 100 cents lower (flatter) than A4=440. This corresponds to lowering the pitch by one semitone, or playing an Eb minor Native American flute. Again, you can play this alone and also simultaneously with the first recording above, to hear the extreme dissonance created by the same melody played simultaneously one semitone apart:

Pentatonic Minor at A=415 Hertz

Clint Goss.

After you start this audio player, it continues to play in a loop. Click the stop button on the audio player to silence this audio stream.

E minor flute of Spalted Maple by Barry Higgins.

![]()

Finally, here is a version using the pitch standard of A4=445 Hertz, another standard that is sometimes used. It is 1.13636% or about 20 cents higher (sharper) than A4=440:

Pentatonic Minor at A=445 Hertz

Clint Goss.

After you start this audio player, it continues to play in a loop. Click the stop button on the audio player to silence this audio stream.

E minor flute of Spalted Maple by Barry Higgins.

![]()

Technical details: The A4=440 recording is the original recording (my playing of the pentatonic minor scale on an E minor Native American flute crafted by Barry Higgins), mixed in Sonar X1 with some reverb from a SonitusFX plugin. The other three recordings were pitch-shifted from a 44.1KHz/16-bit stereo source in Audacity 2.0.3 using a “Change Pitch without Changing Tempo” plugin by Vaughn Johnson and Dominic Mazzoni, which in turn uses SoundTouch, by Olli Parviainen. All files were then converted in dBPowerAmp's dmc tool to variable bit rate MP3 files using the Lame converter version 3.98r.

What is “grandfather tuning”?

This is a general term for a traditional method of crafting flutes. The finger holes and direction holes are layed out on the flute using the body measurements of the maker or player.

See Finger Hole Placement / Grandfather Tuning for a description of this method.

What is “mode 4” or “mode 1/4”?

TBD

Maintenance

How do I care for my Native American flute?

The primary issues are maintaining the structure and finish of the instrument and keeping the flute sanitary. The primary resource for these issues is the maker who origianally crafted the instrument. Always refer to them regarding care instructions. For each flute, it's a good idea to write down or print out (a) the material(s) and finish(es) used on the instrument and (b) the original maker's care instructions. Keep these notes with the instrument.

In general, unless it contradicts information from the original maker of the instrument, here are some guidelines that apply to virtually all Native American flutes:

- Protect the instrument from significant and/or rapid changes in temperature. This means in particular that it is unwise to leave a Native American flute in your vehicle (unless you are in the car) or in the trunk of a vehicle (whether you are in the car or not).

- Protect the instrument from physical damage. A soft “flute sock” combined with a hard-shell carrying case are worthwhile investments.

- Do not play a particular Native American flute more than 15–30 minutes each day. Excessive playing causes the wood to swell, the flute to “water out”, and encourages microbial growth.

- Allow a flute to fully dry out after playing. Until a flute is fully dry, do not store it in a small, enclosed space (such as a flute sock or carrying case).

- Keep flutes out of direct sunlight.

- If a flute has not been played in a while, consider that the inside might need to be oiled. Whether a flute needs to be oiled is highly dependent on the materials and finsh used on the flute — consult the original maker of the instrument.

Most other issues of maintenance should be addressed by the original maker. Here are some particular questions to ask:

- What material(s) is the flute made from?

- What finish(es) are used on the flute?

- How should I care for the finish?

- Should I apply oil or other treatments to the flute?

- How do I remove and re-secure the block of the flute? (a demonstration by the original maker or an experienced flute player is a good idea.)

- What should I do if I find a crack in the flute?

Do I really have to take the block off each time to let the block and flue dry out?

TBD

What should I do if I find a crack in my Native American flute?

Consult the original maker of the instrument. If that is not possible, seek the advice of an experienced flute maker or player.

In general, I have found that using any form of filler that hardens is a bad idea. As it was explained to me by Kai Mayberger of White Raven Drums, a crack in wood tends to expand and contract with varying moisture. If you insert a hard filler, it acts as a wedge when the split contracts. This can cause the split to expand lengthwise.

Some people have successfully used beeswax to fill a split. However, if you must tackle a crack yourself, consider binding the flute.

How do I stop “stuff” from growing inside my flute?

TBD

How do I eliminate “stuff” that has already started to grow inside my flute?

One day you look down the breath hole of your flute to a disturbing sight. It may be green or white or brown or purple, with fancy shapes and fuzzy surfaces. A rich garden growing on the moisture of your breath. It does not belong there.

TBD

Should I oil my flute occasionally? If so, what oil should I use?

TBD

On the Road

What's the best way to transport my flutes when away from home?

TBD

What's are options for holding my flutes at flute circles and performances?

TBD

Recording

What's the best way to record my own playing?

The answer to this is highly dependent on your goals for recording, your budget, your patience, and how comfortable you are with technology. The good thing is that there is a vast range of options for recording, and you can probably find a setup that suits your needs and can support your musicality.

If most of your interactions with technology end in frustration and a feeling that “I must be stupid”, then a simple setup will best serve your musicality.

TBD.

What is the best microphone to record Native American flute playing?

TBD.

Crafting

Please see the separate FAQ about Crafting Native American Flutes.

Writing and Naming Conventions

What is the proper capitalization for the name of the instrument?

In text: “Native American flute”, since only proper adjectives that are portions of the name of a musical instrument are capitalized ([CMS 2003], pages 366–377). In a title in which all words are capitalized: “Native American Flute”.

Is the term “NAF” appropriate as a shorthand?

While “NAF” is used as a colloquial shorthand for the instrument when in a community of people who are familiar with the instrument, it is generally better to spell out “Native American flute”. Use of a TLA that is not familiar can cause confusion (“TLA” means “Three-Letter Acronym”). And, even if you are writing to a flute-knowledgable group such as a newsgroup, those messages are often indexed and have a long lifespan outside the newsgroup. (Kathleen Joyce-Grendahl, personal communication, 2010).

Connecting

How do I connect with other flute players?

Flute Circles

Gatherings

Schools

Organizations

Yahoo Newsgroups

Montana?

PalTalk

How do I find a flute circle?

TBD

|

To cite this page on Wikipedia: <ref name="Goss_2022_faq"> {{cite web |last=Goss |first=Clint |title=FAQ for the Native American Flute |url=http://www.Flutopedia.com/faq.htm |date=7 June 2022 |website=Flutopedia |access-date=<YOUR RETRIEVAL DATE> }}</ref> |

. This is a characteristic key signature for music written in Nakai tablature.

. This is a characteristic key signature for music written in Nakai tablature.